A “PRACTICAL” THEORETICAL MODEL FOR TEACHING SPORT-EVENT MANAGEMENT

Authors: Richard M. Southall, University of South Carolina, Mark S. Nagel, University of South Carolina, Deborah J. Southall, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Robin Ammon, University of South Dakota, and James T. Reese, Drexel University

Abstract

Sport event management, which utilizes modern communication and information technologies, has become an interdisciplinary field. Metadiscrete experiential learning experiences provide increased learning acquisition, since students find themselves in real-world event-management settings. Using a conceptual event-management model to examine a sport event allows students to examine the event from many functional-area perspectives. Within a sport event many “projects” or facets (e.g., strategizing, planning, realizing, controlling) come together during an event. This article provides a model for teaching sport event management in a workable manner, blending theory and practice in order to increase student learning.

INTRODUCTION

A Model for Teaching Sport-Event Management

A cursory examination of the headlines surrounding sport events often reveals event-management challenges, mishaps, and mistakes. In 2013, Major League Baseball’s (MLB) New York Yankees endured a public-relations fiasco when a delayed shipment of Mariano Rivera bobble head dolls resulted in the club having no bobble heads to give away, but plenty of upset fans (Petchesky, 2013). During the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, a variety of problems occurred including stray dogs roaming the Olympic Village, a failure of the 5th Olympic ring to “expand” during the Opening Ceremonies, and numerous construction issues throughout the city (Ilich, 2014). When one of the most financially successful Major League Baseball (MLB) teams and an Olympic Games that cost over $51 billion to operate have event problems, there is a clear indication that event organizers can be more proficient in their endeavors. An event-management class’s ultimate objective in an event-management class is to provide students with a fundamental understanding of the event-management process, in order to minimize the likelihood of their being involved in such an occurrence.

Sport event management is an interdisciplinary endeavor, requiring knowledge and skills associated with marketing, logistics, finance, organizational dynamics, and management. It also requires effective communication between internal and external stakeholders. Thomas, Hermes and Loos (2008) defined event management as “…the coordination of all of the tasks and activities necessary for the execution of an event regarding its strategy, planning, implementation and control, based on the principles of event marketing and the methods of project management” (p. 40). Sport event management coursework is a staple of almost every sport management program, since preparing students to work in the sport industry necessitates a solid grasp of event management. However, the manner in which this content is taught varies considerably at different colleges and universities (Eagleman & McNary, 2010). Though the use of event management textbooks and other written materials is important, scholars have noted providing students with practical experience and placing them in charge of planning and operating an event is an effective pedagogical strategy (Southall, Nagel, LeGrande, & Han, 2003; Verhaar & Eshel, 2013). Ensuring students actively are involved in executing an event provides an opportunity for them to apply theoretical foundations to practical situations.

This paper focuses on strategies for providing a pedagogical model to plan, organize and manage planned “special” sport events in an educational setting. As noted by Getz (1997), special events occur either on a one-time or set schedule; they are not spontaneous unplanned events. Consequently, if formulated properly, sport event management courses allow students to gain practical experience in “special” sport event planning and coordination (i.e., execution). If combined with a strong theoretical foundation, planning and executing a special sport event allows students to maximize their learning experience (Southall et al., 2003). Within this setting, a major challenge is effectively combining theory and practice.

The event management educational model presented in this paper has evolved over the past decade and has been applied in a variety of practical settings. This integrated pedagogical structure incorporates elements of three theoretical frameworks: Southall et al.’s (2003) metadiscrete experiential learning, MacAloon’s (1984) spectacle frame, and Nufer’s (2002) event-management domain. The resultant archetypal event-management pedagogical model can be used to guide sport-management students through the planning, organizing and management process of a small-scale or mega event. It can also be utilized in online, blended or traditional class settings. After briefly discussing each theoretical framework, this paper will offer general guidelines for applying the pedagogical model to a student-planned event.

Theoretical Frameworks

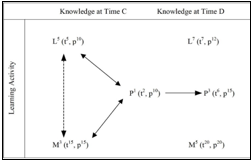

Metadiscrete Experiential Learning. In 2003, Southall et al. proposed a now widely used metadiscrete experiential learning model that provides “…the sport industry with entry-level employees better able to utilize theoretical constructs in the practical work place and graduate students better able to construct theoretical concepts to answer practical questions” (p. 30). As Figure 1 illustrates, metadiscrete sport event-management experiences provide increased learning acquisition based upon students being put in real-world event-management settings in which they must solve actual problems. These common “work” experiences occur within “practical and theoretical frameworks familiar to both” (Southall et al., 2013, p. 30) and result in more effective theoretical and practical linkage.

Figure 1. Metadiscrete Experiential Learning

In a metadiscrete experiential learning environment, a faculty-mentor (who possesses theoretical knowledge and practical experience) provides students with theoretical perspectives from which to view practical sport-event situations (Southall et al., 2003). A metadiscrete framework involves studying a previously held event, or planning, organizing and managing a forthcoming sport event from both practical and conceptual perspectives. Metadiscrete instruction requires educators to use appropriate theories to provide context for their personal practical experiences (Southall et al., 2003). This use of theory to inform practice allows a faculty-mentor to adapt their curriculum to a variety of events and course settings. Within a metadiscrete pedagogical setting, the following two theoretical tools - the Festival Frame and Event Conceptual Model- are very useful in providing a theoretical foundation from which instructors can successfully create a learning environment in which students can maximize their understanding of event management.

Spectacle Frame. In its simplest form, MacAloon’s (1984) festival frame can be conceptualized as a series of concentric circles that allow festival or event planners (as well as students) to “astral project” and travel – in time and distance – “through an event,” while focusing their attention on the experiences of spectators, sponsors, vendors, and/or participants. In today’s technological setting, it would be as if a spectator was moving from the “outer circle” of an event to the “center of the action,” with a flip camera on top of his or her head, chronicling the entire experience. For students – as future sport-event managers – MacAloon’s model provides a mental frame through which to view an event (e.g., sport event or festival), from its outer physical reaches (e.g., airport, mass transit system, parking lots) to areas more commonly associated with a sport event (e.g., main entrance, concourses, spectator-seating, locker rooms). As they “travel” through an event, students must conceptualize the event in its totality, attempting to “see” the needs of both geographic and functional areas. In addition, by analyzing needs and preparing checklists for each event area, students can better recognize interconnections between various functional areas and understand how the event’s various micro aspects combine to form the actual sport event.

The simplicity of the festival frame is one of its strengths, as new technology is developed and the festival-frame experience is extended, new frames can be added to the frame. For example, before the proliferation of the Internet, tickets were typically purchased at an on-site box office or over the telephone. As a result, prior to the 1990s a student-developed festival frame specific to the functional area of ticket sales would likely not have included online primary and/or secondary ticket sales elements, but would only include an on-site box-office, remote-location ticket kiosks, or a ticket-sales call-center. However, in teaching sport event management in the 21st century, such elements are essential components of a sport-festival frame. An example of a festival frame that has been used in a sport marketing and sport-event management course can be found in Figure 2. The festival frame’s adaptability is one of its strengths. While some may view the festival frame as a teaching tool and not a theoretical framework, inherent in the concept of a theoretical framework is allowing those who use the framework (e.g., researchers, teachers, or practitioners) to test the theory and describe results. The festival frame and event conceptual model described in the next section are consistent with Southall et al.’s (2003) contention that combining theory and practice results in superior learning outcomes.

Figure 2. Sport Event Festival Frame

Event Management Domain. In addition to being able to travel through a sport event, it is important that students conceptualize key event elements. Utilizing this type of conceptual model allows students to take an event and examine it from various functional-area perspectives. The concept is utilized in structural engineering, where it is referred to as a Building Information Modeling (BIM) process (Autodesk, 2013). Modern structural design and engineering software allows architects and engineers working on a design for a high-rise building to visualize and simulate a building’s design before actually constructing the building. Through visualization and simulation tools, such software allows construction-management teams to more efficiently and effectively design and analyze projects. However, while it is feasible for construction companies and architectural firms to purchase a perpetual license for an Autodesk AutoCAD software suite, few sport-management professors have $5,000 available to purchase a software package of this type and adapt it for use in a sport-event management class.

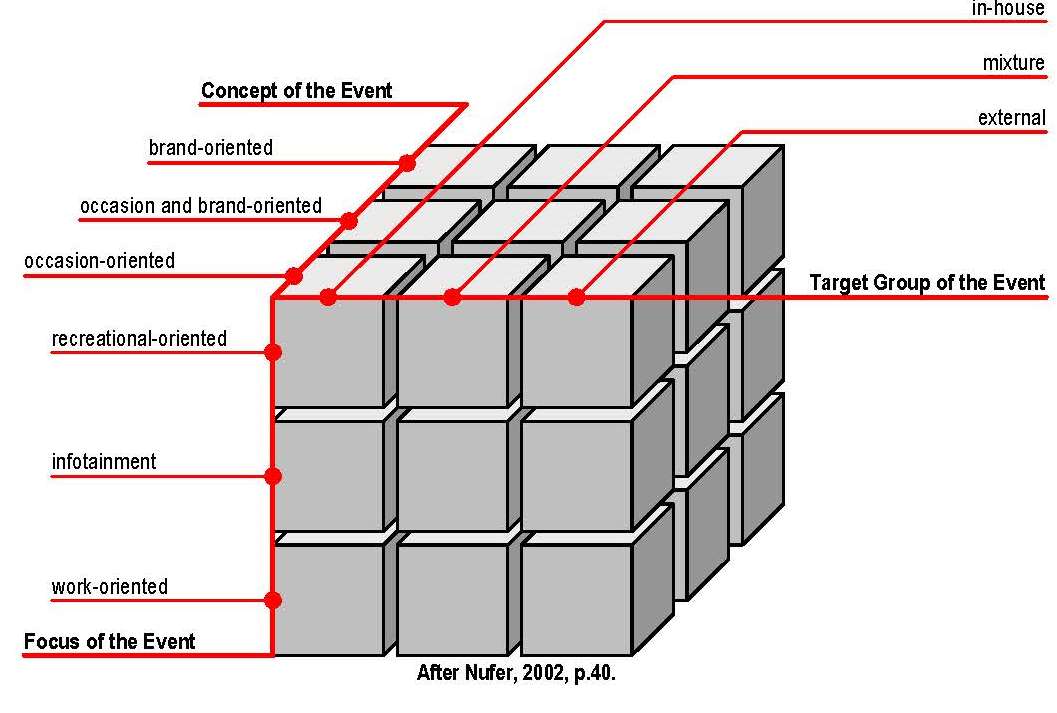

While utilizing an AutoCAD program is an expensive undertaking, Nufer’s (2002) Event Conceptual Model can be easily reproduced and utilized. The model breaks down an event into three main elements: (a) target group, (b) focus, and (c) concept (see Figure 3). All three categories are interrelated, but each focuses on a different event classification dimension. Combining or differentiating between the model’s various categories and sub-categories allows students to create a unique event conceptual map, which can be amended throughout the event’s planning and execution. Since Nufer’s model is adaptable, it can be applied to a variety of sport or entertainment events

Figure 3. Even Conceptualization Model

Target Group. As noted by Nufer (2002), a critical component of an event is the target group or groups, which will participate or be spectators. As students begin thinking about a special event, one method of differentiating the activity is by determining the event’s various target groups. An event may be public (National Football League [NFL] Punt, Pass and Kick) or private (company 18-hole golf tournament). It may be corporate focused (Dew Tour), or designed to support a specific product or brand (Susan G Komen Race for the Cure). It may also be a niche event, designed for only knowledgeable fans or participants (Rocky Mountain Endurance Races) or designed to generate revenue by appealing to a group of consumers (Hoop It Up). An event may have a combination of target groups, or certain aspects of the event may – in fact – target specific smaller, more precise groups (Tough Mudder). Conceptualizing the various target groups “forces” students to look at an event through the target groups’ eyes. Doing so changes the focus of the event.

A sport event’s target groups include on- and off-site participants, customers, and partners. The on-site target groups may include not only in-stadia participants and spectators but also advertisers, sponsors, and vendors. The off-site stakeholders may include domestic or international television, radio, or Internet viewers. A list of target groups may be large or small. What is important is that students use this category to begin identifying the many stakeholder groups for which the event is targeted. Target-group analysis may likely be an ongoing process, since an event’s target groups may change as the event planning process continues.

Focus of the Event. Another facet of Nufer’s (2002) event classification model is determining the primary and secondary event foci. Some questions that students should ask include:

· Is the event designed to generate revenue?

· Is the event intended to inform as well as entertain?

· Is the event a corporate work event?

· Is the event participant or spectator focused, or both?

· Is the event a made-for-television event?

· Is the event going to be broadcast to a remote audience?

· Is the event focused on marketing a product?

These questions help students conceptualize the interconnection of event marketing and sponsorship opportunities and look beyond the within-the-lines or on-the-court event elements. For instance, there are numerous long-distance running races that occur throughout the United States. However, some races may have a primary focus toward determining the top runners in the field while others may have a primary focus toward having fun. For example, both the New York City Marathon and the San Francisco Bay to Breakers attract thousands of runners to their events. Though the New York City Marathon attracts runners of varying ability, the race tends to focus upon elite runners attempting to win the race and other participants working to achieve their personal bests. However, the Bay to Breakers is a different type of race. Though there are runners who are trying to win the event or run their best time, the primary focus of the race is having a good time and seeing what types of bizarre costumes participants will create. By knowing the foci of the event, organizers can better target pertinent event stakeholders and can more effectively execute various event tasks (marketing, security, sponsorship, etc.). This category is closely aligned with and consistent with MacAloon’s (1984) festival frame. By asking these and other pertinent focus questions, students will be more easily able to conceptualize how and why various functional areas should be organized.

Concept of the Event. In addition to target group and focus analysis, students should conceptualize an event’s orientation. In other words, is a special event an occasion, a brand, or a combination? This is, in some ways, closely aligned with an event’s focus, but there can be subtle differences. For instance, an event may be viewed as a for-profit, brand-oriented event within the organization, but viewed as an “occasion” by some participants or spectators. While the NFL Super Bowl is the league’s championship game, some attendees and viewers think of it more as a “party” rather than just a sport event. There are a variety of events before, during, and after the game. In fact, sub-events may each have a different concept, which in many cases has little to do with the sport of football. Students should be aware a sport event might have several associated concepts. In addition, throughout an event various concepts may take “center stage.” Since highlighting an event’s various concepts is part of marketing an event to internal and external target groups, this category is not discussed in isolation. The interrelated nature of event categories is reflected in the three-dimensional nature of Figure 3.

Once the target, concept, and focus of the event have been identified, the event manager can proceed with the various micro processes of planning for the event. For every event activity, the event manager will have an established basis for specific details. The use of Nufer’s model, particularly when used in tandem with MacAloon’s (1984) festival frame, provides a strong theoretical basis for event management.

Teaching Event Management

Having conceptualized a three-part event management model, the next step is to outline a process for allowing students to organize various learning domains according to contextual criteria, and transitioning from macro to micro foci. This focal disaggregation and re-aggregation allows students to use relevant data at a later date, adapt good ideas, follow tips, and optimize event-management strategies for their individual event’s needs (Schwandner, 2004).

Consistent with Southall et al.’s (2003) metadiscrete experiential learning model, at the conclusion of a sport event management course taught in this fashion, students should have developed competencies in event strategizing, planning, realizing, controlling and managing. Students should be able to develop, execute and control events involving specialized functional areas characterized by chronological and logical interdependencies, as well as personnel interrelations. The first phase is event strategizing.

Event Strategizing. This first planning phase or stage involves identifying and solving basic problems. Utilizing MacAloon’s festival frame and Nufer’s categories as conceptual tools, students are encouraged to address and solve rudimentary problems, keeping in mind the event’s focus, concept, and target groups. In order to determine if, after the event is completed, it has achieved its goals, measurable objectives, strategies and tactics should be identified and catalogued well before the event occurs. Goals and objectives can be operationalized through the entire process and connected to communication and event-marketing strategies. An event’s structure must be consistent with its strategic planning. For example, if one of the goals of the event is to generate local or national publicity, then a list of targeted media outlets should be developed by the media relations functional area staff. From this list, publicity objectives (e.g., a specific number and type of mentions or stories) should be determined. Specific strategies and tactics for achieving these objectives can then be articulated. A checklist can then be constructed that specifies media relations tactics to be implemented.

In addition, large demographic groups should be defined and targeted as primary and secondary. A simple, but extremely useful, exercise is to conduct a situational or SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis. This procedure often crystalizes Nufer’s categories for students. In addition, such strategizing delineates the general economic, financial, physical, social or organizational conditions that may constrain the event.

Defining the “size” and scope of an event occurs in this stage. Table 1 details a variety of questions that should be asked both by the event management team (Note: Typically an event management team is comprised of the event’s leaders or directors, who have responsibility for the event’s overall execution and every other student who will be responsible for some aspect of the event.)

The answer to the aforementioned questions and many others must be undertaken before the event planners can proceed to the next steps where specific tasks are assigned and executed. If there are not satisfactory answers to the questions noted in Table 1, the event is not likely to be a success. Though few event planners would proceed if the initial strategic analysis revealed fundamental flaws in an event’s overall strategy, in some cases, entrepreneurs might proceed if there are only a few potential areas of concern. Ideally, the sport event management instructor should explain how these initial strategy questions could lead to an initial event idea being scuttled due to a low likelihood of success. The following planning segments are dependent on this initial strategizing.

Table 1. Event Strategizing Questions

|

Event Strategizing Questions |

|

Is the event private or public? Is it a ticketed event? What type of people will the event attract as participants and/or spectators? Will those people have special needs (e.g., medical, security, disability, etc.)? Does the event management team have sufficient resources to execute the event? If sufficient resources (whether human, financial, technological, etc.) are not currently present, can they be procured? What marketplace factors exist that will influence the event’s operation and chance of success (e.g., government regulations, competitors, local infrastructure, etc.)? What type of facility (or facilities) will enhance the event’s opportunity to maximize success? Are those facilities available? What financial considerations must be evaluated when planning the initial idea of the event? What are the primary vulnerabilities of the event and how can they be controlled? What are the hazards (e.g., man-made or natural) to the staff, facility or guests? |

Event Planning. After the strategic planning phase has determined that the event has a strong likelihood of achieving success and preliminary macro questions have been answered, the elements of event planning can occur. Obviously, securing the event venue(s) is a critical step. Without a venue for the event, it is difficult to prepare for all of the event’s functional areas. The cost of procuring the venue will have an important impact upon the financial success of the event and the venue’s attributes including size, amenities, available equipment and various other characteristics will help guide the event planners to determine micro activities associated with the event.

With the facility secured, a variety of controlling activities must be established and event functional areas created. Each functional area will need to identify and develop procedures relevant to their areas of responsibility. A critical aspect of each event functional area is establishing leaders who will provide guidance and maintain performance accountability for the members. Each functional area needs to estimate its personnel and financial needs in the early event-planning phase so preparations can be made to address budgetary issues. Each area should have regular meetings to insure progress toward established goals and objectives.

As each individual functional-area team is created and plans for the event are established, a master event timeline of responsibilities and timelines for completion should be developed. Such a timeline is often called a Gantt chart, since the first modern use of such a timeline is attributed to Henry Gantt in the early part of the 20th century. The creation of such a master schedule encourages each functional-area team to think through their tasks and determine not only in what order their team’s tasks need to occur, but also how their tasks may impact and be impacted by tasks assigned to other functional areas.

Just as individual functional area members report and discuss plans with a functional-area manager/coordinator, functional area heads report and discuss their functional-area plans with the event’s executive team. The event’s managerial hierarchy can be clearly delineated through developing an organizational chart. Having students develop a graphic depiction of reporting protocol and lines of communication helps functional-area teams adhere to developed timelines or schedules and maintains their developed plan in accordance with overall event concepts. Constructing an organizational chart is not the end of this process, but only the beginning. Ongoing and systematic communication between functional-area teams and the executive team helps insure each team is aware how their area is affected by and impacts the event’s overall capabilities (e.g., staffing, marketing, budget).

As functional area teams develop plans, checklists must be established. These checklists not only assist the team in knowing what they need to accomplish, but can also be utilized by other team members if changes in personnel occur. For example, if the event team planning hospitality activities loses its leader due to illness, the rest of the event teams will have a quick reference guide to check to see what must be done. Checklists create a measure of accountability among team members. In addition, when checklists are developed and distributed to other event teams, areas of crossover and duplication can be identified. For instance, if both the event registration team and the sponsorship team identify pre-event setup needs of a truck to transport materials, the teams can discuss utilizing one truck to avoid duplicate expenses.

Event Realization. Legendary World War II German Field Marshall Erwin Rommel was thought to have remarked, “Every plan is good until the first shot is fired.” More recently, the American boxer and sometimes philosopher, Mike Tyson, summarized this idea when he noted, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth” (Berardino, 2012, para. 2). Ultimately, the greatest event plan must be executed, and in some cases, superb, well-designed plans are not implemented properly once an event has begun. A variety of challenges occur before and during an event, including items that are in direct control of the event team, such as event staff failing to arrive for work or issues that are beyond anyone’s direct control (e.g., inclement weather).

Though not every potential problem situation can be predicted, successful event operations are much more likely to be realized if the executive event management team and each functional area emphasize the process of addressing various event outcomes. Created checklists should be subject to continual review and revision. This process can provide a context for event staff members developing the ability to think and act, rather than be inextricably bound to a single operating procedure. The event executive team should ensure policies and procedures are developed and in place, but should also emphasize the need for short-term problem solving by functional-area staff members. In nearly every event a question is asked or a situation occurs that requires a general thought process prior to execution. Certainly, veteran event staff members are better equipped to handle these types of situations, but in some cases veterans are not available. Ideally, in a sport-event-management classroom setting, there are some students who have previously worked on that specific event or something similar. In some cases, coordination between undergraduate and graduate programs can create a learning environment in which event “returnees” and “rookies” learn with – and from – each other.

Even if there are no event veterans, creating an environment where students are prepared and confident is crucial to an event’s success. The best way to create an environment where students are engaged and motivated problem solvers is to systematically table top various event functional area procedures.

A table top exercise is a brainstorming exercise that encourages participation from all members within a functional area or the entire event staff. Developed event procedures can be reviewed and tested during a table top exercise. The exercise focuses on the steps involved in activating the event. Various scenarios can be developed that allow participants to breakdown what steps need to be taken to complete the procedure. “Table topping” (as it is often called) can be limited to functional area heads or may involve all event staff. (Note: Table top elements are also discussed in the subsequent lab packet section.)

The table topping process enables event workers to visualize event flow and more likely predict where potential problems might occur. In most cases, individual event functional areas should table top its area of responsibility. Once every team has conducted one or more table top exercises, at least one dress rehearsal for the event should occur. This dress rehearsal is vital because individual teams may develop, practice, and perfect their actions and a reaction for their area, but executing individual activities in a vacuum is not going to occur during the event. Each of these areas must be coordinated so they can effectively perform their duties once the event begins. For example, concessions and the media-relations teams will develop and practice plans to provide ingress and egress for visiting vendors and media members. However, if such plans are not coordinated, teams may not identify potential “back-stage” access, restricted areas, and event set-up and tear down conflicts.

It is critical that the dress rehearsal include all aspects of the event, not just the “main event” elements. Most events do not just involve a sporting event, but also involve pre and post-event activities. Ceremonial pre-event elements such as the introduction of prominent attendees and sponsors may involve a special public address system not utilized during the main part of the event. Dismantling of the post-event equipment may require special tools that will not be present at the facility unless the event team remembers to bring them. Ultimately, a dress rehearsal is intended to prepare functional-area teams to execute all event aspects in real time.

Event Controlling. Though most students initially think of event controlling in terms of the various functional areas (e.g., parking, ticketing, security), it first involves control of the planning process, information, organizational staff members, and, often and most importantly, costs. Event controlling spans all domains and phases of the event and does not begin with the event, but rather begins with the first meeting to propose a potential event.

Event managers need to recognize deviations that occur in the event plans and identify causes of those deviations. Though the pre-event planning process needs to be thorough, there is rarely a perfect plan executed exactly as scheduled. Deviations can occur and they need not create a potential disaster. Of particular concern is controlling the expenses that will accrue from the various event activities. Sport event management instructors must continually emphasize the need to control costs. Of particular concern for students is understanding that a component of the budget control process is incorporating the “when” aspect of revenues and expenses. A thoroughly planned event budget will not function properly in practice unless enough revenues are generated in a timely manner to cover required event expenses (Brown, Rascher, Nagel, & McEvoy, 2010). Instructors must insist students learn that the timing of payments from sponsor and media contracts is nearly as important as the amount those contracts mandate.

There is often euphoria when the competition or other core aspect of an event begins. From this point, until the event is concluded, it is critical that control of the budget and other event functional areas is maintained. It is crucial that staff understand the event continues after the competitors have left the playing field and spectators, sponsors, and media members have gone home. Every functional-area team needs to effectively close out its areas of responsibility. An accurate final accounting must be completed and any delinquent accounts addressed. Ultimately, the final phase of event controlling involves gathering large amounts of data that will be utilized to prepare the final overall event evaluation.

Ultimately, event management involves synthesizing many functional area responsibilities. Within a sport event many “projects” or facets (e.g., strategizing, planning, realizing, controlling) come together during an event. Managing the merger of these components is the essence of sport event management. Event management occurs simultaneously and continuously within a sport event framework (Ammon, Southall, & Nagel, 2010). It is a process that is not black and white, but a series of responses to intricate situations. Sport event management involves using human resources to respond to the unfolding of an event in real time. Regardless of whether the event is a mega sport event or a small-scale charity tournament, understanding the domains and how they are interrelated allows students to make the transition from a staff member or volunteer to a sport-event manager.

Sport Event Management Instruction in Practice: Lab Packet

When implementing this pedagogical model, a series of guided activities supplement instructor lectures. While the minutiae of such activities are best left to each individual instructor, this section offers some general guidelines and suggestions for combining theoretical lecture/discussions with student-directed activities to develop a one or two semester course. By combining theory and practice, a more well-managed sport event and increased student learning are the likely outcomes.

Time restrictions and monetary limitations may preclude planning, organizing, and managing a large-scale sport event as part of a semester-long undergraduate sport-event management course. However, students can still be exposed to sport-event management fundamentals by activating a smaller, and consequently more manageable, sport event.

Constructing a lab packet that provides a roadmap for students to work from a macro to micro foci is crucial for moving from theory to practice. Any lab packet should be continually updated, reflecting the adoption of new ideas from colleagues and sport organizations. Utilizing “tips of the trade” will allow development of a dynamic event management curriculum that keeps up with the newest best practices. Some possible lab packet elements are outlined below. In keeping with the use of checklists discussed above, the following sections may be included. For each section, appropriate checklists can be developed:

Event Knowledge Test. One of the most important skills for any member of an organization is product knowledge (Irwin, Southall, & Sutton, 2007). Developing an event-knowledge test (EKT) for a sport-event management class is designed to provide students with an opportunity to review an event’s marketing mix (i.e., product, price, place, promotion, people, public relations). Since many students will have completed a sport marketing class, this situational analysis will be a familiar activity. Having students develop and take an EKT will ensure they have an appropriate understanding of a specific sport event and the various functional areas with which they may be associated. The required level of event knowledge may vary, depending on whether students are developing a charity tournament, or serving as event-operations staff/volunteers for home games of their university’s athletic team or a local minor-league franchise. If the developed event (e.g., golf tournament, three-on-three basketball tournament) is designed to benefit a chosen non-profit or charitable organization, every student must have a thorough knowledge of the designated beneficiary organization as well. In addition to benefiting a charitable organization, it is often advantageous to partner with a professional sport organization or athletic department to provide students with real-world event operations experience. In this case, students should be expected to have a complete knowledge of the franchise or department, including such elements as its history, staff, schedule, and ticket prices.

Developing a lab packet with sport-event management activities, conducting on-site visits, encouraging students to shadow staff members, and facilitating group discussions are all strategies that will increase event knowledge. In addition, a variety of assessment strategies can be regularly administered (e.g., oral quizzes, weekly exams, and a cumulative product knowledge test). High levels of event knowledge, coupled with motivational activities designed to build a sense of event ownership throughout the semester, will increase the likelihood that the event will be successful.

Developing Objectives and Strategies-To-Tactics Questions. As part of developing an EKT, the class may engage in an extended questioning/brainstorming session designed to generate a lengthy set of product-knowledge and event-specific questions. Some possible questions might include:

· What are the key messages the promotional plan should communicate?

· How can publicity, promotion, and advertising activities disseminate messages? In what media should stories be placed?

· How can elements of the event(s) be utilized as publicity and promotional engines? What compelling stories can be told? What can be done to make the event newsworthy?

· How can stakeholders help promote the event’s message(s)?

· What long-term legacies can the event provide? What opportunities are there for future events? Are there other related events that can be developed?

· How can the event be clarified in the mind of attendees and the public?

· How can promotional strategies be developed and pursued? What resources are required? Are there sufficient resources? If not, where/how are additional resources obtained?

These initial questions may lead to an entire new set of questions:

· How can the event be made interesting and exciting for attendees?

· How can the event registration, access, and comfort be improved and/or maintained?

· How can value be added for attendees?

· How can new event attendees be secured? How can first-time attendees be convinced to become returnees?

· What events/organizations can be utilized via cross-promotions to build awareness and attendance?

· How can the general public be educated about the event?

· How can media be encouraged to cover the event?

Developing partnerships with relevant stakeholders is a crucial concept for students to grasp. Consequently, there may be several questions related to partnership development that might be proposed:

· How can the event be used to establish and strengthen ties to stakeholders?

· Are there opportunities to provide unique access to event attendees or special hospitality opportunities that demonstrate sponsor value?

· How can the event be viewed as showcases for potential future sponsors/donors? Are there opportunities to provide prospective future partners with one or more perquisites of a current sponsor that will demonstrate the value of joining a “family” of sponsors?

· Are there opportunities to offer a partner added value (e.g., pre- and post-event advertising, on-site signage, participant awards and ceremonies, special segments, giveaways, staff uniforms, event program, save-the-date cards, flyers, emails, website, posters)?

In addition, while revenue-generation may not be the event’s focus, it is important that students appreciate and discuss the proverbial “bottom line” at the outset. For a class-developed event, asking such money questions is vitally important, since most such events involve zero-based budgeting. Some revenue questions may include:

· What is an appropriate admission? Should registrations be tiered?

· Is it appropriate or desirable to sell event-themed merchandise? What type(s) of merchandise? At what prices?

· How many, for how much, and to whom should sponsorships be offered?

· Can sponsorships be bundled? Should “low-cost” packages for new sponsors who want to test their association with the event be developed?

· Are multi-year sponsorships desirable?

· Should year-round sponsorship partnerships be pursued (to provide benefits through association with other events or class/program activities)?

· What advertisement packages may be available? Who will sell the ads and to whom will they be sold?

Developing Checklists. Checklists are fundamentally problem-solving tools. While problems may be simple, complicated or complex, Gawande (2010) noted checklists are “…quick and simple tools aimed to buttress the skills of expert professionals” (p. 128). Students should look upon checklists not as replacing managerial skills, but as instruments for making sure mundane tasks are not forgotten. Checklists allow sport managers to focus on the “hard stuff!” A checklist should be simple, measurable and replicable. Every item should improve communication among team members. Every member of each functional area should be involved in the checklist-creation process.

In addition, since the questioning activity outlined above should have produced measurable objectives, checklist items should address developed objectives. Checklists should be designed so that they can be read aloud and verbally checked. To assure a checklist does not impede an event’s workflow, it should use simple language and sentence structure, so it can be referred to during natural breaks. As long as critical areas will not be omitted, limiting a checklist to one page is optimal. Flipping through multiple pages for a single checklist defeats a primary purpose of a checklist. The checklist should allow for errors to be detected and easily corrected.

While a checklist is a crucial event-management tool and should be an integral part of a sport-event management course, it is important to remember a checklist does not replace a thorough staff briefing and discussion of possible scenarios. A checklist is a static list; sport events are dynamic and fluid. Student will still need to talk through the “hard stuff” and address critical issues. More than anything, a checklist can be a valuable change agent within a class setting. The act of developing and listing steps on a checklist often raises questions about the order of listed tasks. Each semester checklist procedures may be slightly redesigned. Such discussion and revision helps empower students and gives them a sense their input is valuable.

A class dynamic that checklists can help moderate is organizational groupthink (Janis, 1982). In many groups one or more dominant individuals may “speak” for the group. This dominance can stem from past experience, physical presence, voice inflection, or many other personality traits. If students feel inhibited from questioning existing policies and procedures, alternative ways of doing things may be ignored. Janus (1982) noted a group is especially vulnerable to groupthink when members from similar backgrounds have no clear decision-making rules and make decisions in an isolated setting. In a class setting, peer pressure or dominant personalities may lead to a deterioration of reality testing. This pressure may result in organizational/team members adhering uncritically to organizational/team/functional area hierarchy and blindly following orders. Too often functional area team members believe doing what they are told (whether in a class or real-world setting) is the safest course of action. Within an organizational setting, a person of lesser rank often finds it difficult to speak up if a “superior” forgets to execute an important procedure. However, if that step is noted on a checklist, it is far easier for the subordinate to help the superior recognize and rectify his or her error (Gawande, 2010).

Consequently, responsibility for checklist development and implementation should be shared among team members. Each section of a checklist should be read aloud. Conducting regular “talk-through” activities allow each team member to double-check each checklist item and each other. Regularly putting processes and procedures under a microscope provides an opportunity to critically examine each task, raise questions, and potentially improve the workflow. Talk-through discussions culminate in more formal table top exercises (See Table top exercises below.).

Developing Functional Areas. Each sport event may have a variety of functional areas. For a semester-long event management class that has decided to plan, organize, and manage a charity golf event, the general functional areas may be subdivided into more specific teams. Some general functional areas may include operations, tournament, registration, marketing, event presentation, and hospitality. Operations may be subdivided into more specific areas of responsibility such as facility operations (e.g., space allocation management, load-in/load-out, labor, signage, first-aid, security, transportation, parking, shipping and receiving, business affairs, accounts payable-receivable, purchasing, and legal). Tournament may include scheduling, course preparations, communications, and marshaling. Registration may be broken down into pre-registration, registration, VIPs, information services, and office services. Marketing is a broad category that encompasses creative services, sponsorship, sales, advertising, promotions, and publicity. Presentation elements include creative rundowns and script development, sponsorship management, talent booking, rehearsal management, and technical production. In addition, it is crucial that hospitality and social events, including receptions and parties before, during, and after an event, are planned, organized, and managed.

Table Top Exercises. As previously discussed, table top exercises are the culmination of many previous course activities. An in-class table top should simulate a specific event element. It may be an emergency situation, a specific procedure related to concessions, or some other event-management facet. Conducting their own table top exercises allows students to discuss and validate their developed plans. Each table top also provides a faculty member with a chance to unobtrusively evaluate student competencies, test established procedures, and develop appropriate training opportunities. Such verification allows for students to determine if their plans are reliable and workable. These activities are crucial in validating the confidence placed in a written plan. Until a plan has been “table topped,” any confidence placed in the integrity of a written plan is just an article of “faith.”

Having developed and taken a product-knowledge test, constructed objectives and strategies-to-tactics guidelines, created functional-area teams, and established checklists, table top participants should have an awareness of their roles and be reasonably comfortable with them. They can visualize and articulate their roles before they are placed in a more stressful situation. This process tests procedures, not students. If students are under-prepared, a table top allows the plan to be criticized, not the students. However, for the instructor a table top identifies students’ lack of preparation and training. Such evaluation can take place while still allowing students to feel comfortable in their roles. Consequently, table top exercises are both evaluation and motivational tools.

Constructing an Event Manual. Constructing an event manual provides an opportunity for students to document the planning, organizing, and managing of the event. It not only provides structure during the entire event-management process, but also provides a step-by-step reflection and evaluation tool for examining the many learning activities that occur during this process. Consistent with metadiscrete experiential learning concepts, continually cataloguing the event by editing and re-editing an event manual throughout the course is an important step that increases student learning (Southall et al., 2003). In addition, functional-area responsibilities can be clearly outlined within the event manual, offering documentation for work experience.

At the conclusion of the semester, students can be provided a pdf of the final event manual, which can become part of their job-interview portfolio. Table 2 details potential event manual sections. Though it is not an exhaustive list, it provides a starting point from which a unique event manual can be created.

Table 2. Potential Event Manual Sections

|

Potential Event Manual Sections |

|

|

1. Event Mission Statement and Objectives |

15. Registration (If applicable) |

|

2. Contact List |

• Pre-Registration |

|

3. Calendar of Critical Dates |

• Day-of-Registration |

|

4. Emergency Procedures |

• VIP Registrations |

|

5. Event Time Line/Schedule |

• Attendee Gifts |

|

6. Organization |

• Office Services |

|

7. Functional-Area Checklist |

16. Presentation |

|

8. Job-Specific Checklists |

• Event Rundowns and Scripts |

|

9. Maps and Floor Plan |

• State Management |

|

10. Event Policies and Procedures |

17. Marketing |

|

11. Risk Management |

• Creative Services |

|

12. Financial Information |

• Business Development |

|

13. Contracts |

• Sponsorship |

|

14. Operations |

• Sales |

|

• Facility Operations |

• Advertising & Promotions |

|

• Transportation |

• Publicity & Media Relations |

|

• Business Affairs |

18. Transportation Plan |

|

|

19. Lodging (if applicable) |

|

|

20. Post-Event Assessment and Reconciliation |

|

|

21. Peer Evaluations |

CONCLUSIONS/IMPLICATIONS

This article concentrated on providing some guidelines for developing a sport-event specific curriculum in a university educational setting. The combination of theoretical and practical elements allows for a course in which undergraduate sport-management students gain practical sport-event management experience and maximize real-world learning. Ultimately, the biggest challenge of teaching event management is effectively combining theory and practice. The developed archetypal event-management pedagogical model can be utilized to guide sport-management students through the sport-event management planning, organizing, and management process.

REFERENCES

Ammon, R., Southall, R. M., & Nagel, M. S. (2010). Sport facility management: Organizing events and mitigating risks (2nd ed.). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Autodesk Inc. (2013). Architecture, engineering & construction structural engineering. Retrieved from http://www.autodesk.com/industry/architecture-engineering-construction/structural-engineering

Berardino, M. (2012, November 9). Mike Tyson explains one of his most famous quotes. SunSentinel. Retrieved from http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/2012-11-09/sports/sfl-mike-tyson-explains-one-of-his-most-famous-quotes-20121109_1_mike-tyson-undisputed-truth-famous-quotes

Brown, M. T., Rascher, D. A., Nagel, M. S., & McEvoy, C. D. (2010). Financial management in the sport industry. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway.

Eagleman, A. N., & McNary, E. L. (2010). What are we teaching our students? A descriptive examination of the current status of undergraduate sport management curriculum in the United States. Sport Management Education Journal, 4(1), 1-17.

Gawande, A. (2010). The checklist manifesto: How to get things right. (Vol. 200). New York: Metropolitan Books.

Getz, D. (1997). Event management & event tourism. New York: Cognizant Communication Corporation.

Ilich, B. (2014, February 10). Sochi problems: 2014 Winter Olympics have plenty of ups and downs. International Business Times. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.com/sochi-problems-2014-winter-olympics-have-plenty-ups-downs-1554317

Irwin, R. L., Southall, R. M., & Sutton, W. A. (2007). Pentagon of sport sales training: A 21st century sport sales training model. Sport Management Education Journal, 1(1), 18-39.

Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes. (2nd ed.). New York: Houghton Mifflin.

MacAloon, J. J. (Ed.). (1984). Rite, drama, festival, spectacle: Rehearsals toward a theory of cultural performance. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

Nufer, G. (2002). Wirkung von event-marketing: Theoretische fundierung und empirische analyse. Wiesbaden: DUV.

Petchesky, B. (2013, September 24). Mariano Rivera bobblehead night is a fiasco. Deadspin. Retrieved from http://deadspin.com/mariano-rivera-bobblehead-night-is-a-fiasco-1379900267

Richmond, M. (2013, November 15-16). The role of table top exercises. Presentation at the International Sail Training and Tall Ships Conference 2013. Retrieved from http://www.sailtraininginternational.org/_uploads/documents/TableTopWorkshop.pdf

Schwandner, G. (2004). Grundlagen - Projektmanagement und organisation. In F. Haase & W. Mäcken (Eds.), Handbuch event-management (pp. 27-45). Munich: Kopaed.

Southall, R. M., Nagel, M. S., LeGrande, D., & Han, M. Y. (2003). Sport management practica: A metadiscrete experiential learning model. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(1), 27-36.

Thomas, O., Hermes, B., & Loos, P. (2008). Reference model-based event management. International Journal of Event Management Research, 4(1), 38-57.

Verhaar, J. & Eshel, I. (2013). Project management: A professional approach to events (3rd Ed.). The Hague: Eleven Publishers.