EXAMINING BODY IMAGE IN RETIRED COLLEGIATE VOLLEYBALL PLAYERS

Authors: Caroline E. Laure, Ed.D., and Nichole Meline, Idaho State University

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the self-perceived body image of female volleyball players more than 10 years after their collegiate playing careers have ended. Utilizing a phenomenological approach, we surveyed and later interviewed ten former collegiate volleyball players ranging in age from 29 to 52. We identified and explored four emergent themes. These were (a) maintaining an athlete identity, (b) focusing on new priorities, (c) physical changes, and (d) body image. Most of the women have maintained their athletic identity to some degree, however new priorities, including work motherhood, have lessened its importance. As a result of the decreased emphasis on sport and the accompanying aging process, the women recognize physical changes, many of which have altered their perception of their overall body image but have not caused a significant amount of distress.

INTRODUCTION

Retirement from collegiate sport can be a distressful event in the life of an athlete. Over the last decade, the transition of an athlete away from the competitive collegiate sport environment has attracted a great deal of research attention (Fuller, 2014; Stephan, Ninot, & Delignières, 2003; Stephan, Torregrosa, & Sanchez, 2006; Warriner & Lavallee, 2008). It has been widely recognized that while the retirement experience is unique for each athlete, most athletes will encounter difficulty with the drastic changes that are likely to occur in their social, professional, and personal lives (Lavallee, Gordon, & Grove, 1997). Researchers also recognize that while the actual retirement is but a single event, some individuals have great difficulty attempting to psychologically separate themselves from their collegiate sport identity (Beamon, 2012).

Athletic identity issues often begin at the time of retirement, as athletes prepare to leave behind the athlete role and assume a new role in life. Athletic identity is defined as “the degree to which an individual identifies with the athlete role” (Brewer, Van Raalte, & Linder, 1993). It is largely constructed by the appearance of the athletes’ physical bodies and their bodies’ ability to perform athletically (Saint-Phard, Van Dorsten, Marx, & York, 1999). Collegiate athletes devote many hours each day to practicing sport-specific skills and conditioning their bodies for optimal sport performance. Great pride is taken in feeling athletically competent. An athlete’s self-worth may center on their own perceptions of their physical capabilities (Saint-Phard et al., 1999).

Researchers North and Lavallee (2004) found that athletes’ primary priority, post-playing career, is seeking employment. Along with new roles in their professional life, these former athletes may find themselves embracing the role of spouse and/or parent. A major reorganization of priorities takes place. The typical day as a college athlete, characterized by hours of practice and workouts, becomes a thing of the past. The athletes’ new professional and personal obligations may leave very little time for a regular exercise program to be followed. Bodily changes, including changes in weight, muscle mass, and physical competencies may occur as a result of the discontinuation of regular, intense training (Stephan, et al., 2006). The natural aging process as well as the possibility of pregnancy in former female athletes also contributes to the occurrence of these bodily changes. If the former athlete perceives these physical changes negatively, their physical self-concept, body image, and overall self-esteem may be adversely affected (Stephan, et al., 2003).

While the body of research concerning transition out of elite and collegiate sport is growing, much of the focus of the current research includes athletic identity, professional development, loss of support systems, and general well-being. To date, little is known about how former athletes experience and perceive the often-inevitable bodily changes that occur post-playing career. It is highly unlikely that retired athletes will continue to follow the strict training schedules of their collegiate playing career (North & Lavallee, 2004). Degradation of physical competencies along with changes to body composition will eventually occur as a result of training cessation. Body image issues, often brought on by negatively perceived bodily changes (e.g. weight gain, loss of muscle mass, bodily pain, etc.) can be severely distressing and might lead an individual to engage in unhealthy behaviors as a way to cope with their body dissatisfaction. Distress as a result of body dissatisfaction can also disrupt an individual’s mental health, making it difficult for them to go about life happily and productively.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the self-perceived body image of female volleyball players more than 10 years after their collegiate playing careers have ended. This study has the potential to benefit collegiate athletes retiring from sport by elucidating the importance of addressing the predictable body composition changes and potential body image disturbances that may occur post-playing career. Currently, many colleges and universities provide their student-athletes with the opportunity to meet with an advisor or specialized psychologist to assist with transitioning into a life after sport. There are also a number of widely used educational programs such as the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) Life Skills program. This program and others similar to it, focus on career planning and arming student-athletes with the skills they will need to succeed in the professional world upon graduation and their coincident retirement from sport (NCAA, 2008). These types of programs need to consider expanding their educational aims to include preparing student-athletes for anticipated physical changes. Further, mental health professionals who work with athletes at colleges and universities should be aware of the potential for unwanted or unexpected physical changes to bring about body dissatisfaction and, in some cases, maladaptive coping behaviors.

BACKGROUND

Body Image

Over the past few decades, prevalence of body dissatisfaction and related concerns (e.g. disordered eating) in athlete and non-athlete populations alike has increased, leading to an abundance of research pertaining to body image and an expansion of the definition of this multidimensional term (Grabe, Ward, & Hyde, 2008) . Researchers now recognize that a person’s body image involves much more than merely the subjective, mental representation of physical appearance. A deeper understanding of this global construct has allowed researchers to tease apart and identify the various components that are encompassed by body image, including terms such as body esteem and body satisfaction (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999). A preoccupation with physical appearance has led many individuals to engage in very negative, damaging behaviors and patterns of thought, creating the need for even more terms to define and classify these things related to body image, such as body distortion, body dysmorphic disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and more (Thompson et al., 1999). In order to understand body image as a whole, it is necessary to first understand some of the key components of body image.

Body esteem and body satisfaction. Body esteem and body satisfaction are two very closely related terms and are often used interchangeably. Body esteem refers to the satisfaction or dissatisfaction a person has with his or her body overall, whereas body satisfaction refers to the satisfaction or dissatisfaction with individual body parts or areas independently (Thompson et al., 1999). It is clear how these two constructs play a large role in the development of one’s body image. Individuals who report body dissatisfaction tend to also reported poor body image. These same individuals are also more likely to report symptoms of depression (Stice & Bearman, 2001). Related research has associated body esteem and body satisfaction with not only depressive symptoms, but also psychosocial functioning, influencing global self-esteem, confidence in social situations, sexual behaviors, and emotional stability (Cash & Fleming, 2002). Further, both body esteem and body satisfaction have been found to influence mental health and overall quality of life (Cash & Fleming, 2002).

Body distortion and related disorders. Body distortion refers to an inaccurate or distorted view of one’s body (Thompson et al., 1999). Typically, individuals who experience body distortion believe they are overweight, when in reality they are either within or below a healthy weight range. Body distortion does not always stem from poor body esteem or body dissatisfaction, but almost always leads to harmful, negative feelings about one’s body, producing significant body image disturbances. When the distortion and the resultant distress is so pervasive that impairs the individual’s day-to-day functioning, it is classified as body dysmorphic disorder (Bjornsson, Didie & Phillips, 2010). Body dysmorphic disorder is often a precursor of eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Stice & Bearman, 2001). Therefore, body distortion is included in the diagnostic criteria for both of the aforementioned eating disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Causes of body image disturbance. A number of theories have been developed in an attempt to explain body image problems. Among these, the sociocultural theory is recognized as the most comprehensive and has gained a great deal of empirical support (Thompson et al., 1999; Campbell & Hausenblas, 2009). This theory centers on the idea that social and cultural factors have a considerable influence on the development and maintenance of a person’s body image (Thompson et al., 1999). The current cultural preference is for a tall, thin, and toned female body. This generally unrealistic body ideal pervades society via social media, television, magazines and other forms of mass media (Flament, Hill, Buckholz, Henderson & Tasca, 2012). For women, this body type is often equated with social acceptance, worth, and happiness (Rodgers, Cabrol, & Paxton, 2011). Campbell and Hausenblas (2009) found that the severity of a woman’s body dissatisfaction is partially predicted by the degree to which her body differs from the current ideal body parameters. Mass media tends to present similar body ideals for athletes as well, with female athletes in advertisements or other media channels appearing to have chiseled arms, abs and legs and a thin aesthetic overall (Fortes, Neves ,Filgueiras, Almeida, & Ferreira, 2013)

Consequences of widespread body image disturbance. Negative body image and related issues affect upwards of 50% of women – in both athlete and non-athlete populations (Fortes, Paes, Neves, Meireles, & Ferreira, 2015) A person’s evaluation of their body contributes to their overall self-concept. A person’s self-perception dictates thoughts, beliefs, behaviors, and feelings. Thus, negative body image can be especially pervasive, both directly and indirectly influencing many aspects of a person’s life. Even seemingly unrelated life domains, such as the ability to confidently carry out everyday tasks and the ability to create and maintain relationships, are impacted by body image experiences (Cash & Fleming, 2002). Among athlete populations, negative body image and perceived variance from the prescribed athletic ideal often leads to disordered eating behaviors and/or compulsive exercise (Greenleaf, Petrie, Reel & Carter, 2010; Haase, 2011). When body image issues result in restrictive eating, especially when coupled with excessive or compulsive exercise, the situation can become life threatening.

The Collegiate Athlete

Athletes represent a unique population characterized by distinctive experiences and stressors, especially in the area of body physique and body image. When comparing college athletes to the general population. There are some notable differences in terms of physical activity and fitness levels as well as body image concerns, when comparing college athletes to the general population.

Physical demands. Compared to the non-athlete population, collegiate athletes are extremely active individuals. The practice regulations put forth by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) state that athletes are allowed to spend 20 hours per week practicing. However, many student-athletes report spending upwards of 25 hours a week practicing, explaining that coaches consistently find ways to get around these rules and regulations in order to increase practice time (Josephs, 2006). In addition to practicing sport-specific skills, athletes typically engage in strength and resistance training and endurance training. The variety and amount of physical activity collegiate athletes engage in leads to notable changes in body composition. More specifically, athlete populations present significant differences in body fat and muscle percentage compared to non-athlete populations (Mazić et al., 2014).

Body image concerns. Much of the research surrounding body image concerns in athlete populations is somewhat conflicting. Some research suggests that pressures to be thin are greater in aesthetic or traditionally feminine sports such as gymnastics, dance, or figure skating (Varnes et al., 2013). While other studies suggest that this pressure exists in the entire culture of women’s sport and the idea that a lean body with high levels of fat-free mass is needed for optimal performance is ubiquitous (Smolak, Murnen & Ruble, 2000; Muscat & Long, 2008). Additionally, female athletes have been identified as an at-risk population for disordered eating, as various studies have shown the increased prevalence of eating disorders in this group (Greenleaf, Petrie, Carter, & Reel, 2009 Sundgot-Borgen & Torstveit, 2003). Still, other researchers have found that as a result of exercise frequency and having a body that more closely represents the current ideal, athletes possess a more positive body image than non-athletes (Hausenblas & Downs, 2001). While some research findings in this area are contradictory, the idea that female athletes experience a great deal of pressure to be in excellent physical condition as a way to optimize athletic performance is supported throughout the entirety of this body of research. The ways in which female athletes cope with and respond to these pressures seems to vary.

Physical Changes

Retirement from sport. An athlete’s retirement from sport can be an especially difficult event for various reasons. Adjusting to a life after sport involves a drastic shift in priorities, responsibilities, aspirations, as well as new social and professional roles. Many ex-athletes struggle to let go of their athletic identity and as a result, identity issues often occur to some degree (Beamon, 2012; Fuller, 2014; Lavallee, Gordon, & Grove, 1997). Part of what contributes to an individual’s athletic identity is their level of athletic competence and superior physical fitness. It has also been suggested that an athlete’s feelings of self-worth and well-being are partially constructed by their perceived physical competencies (Saint-Phard, Van Dorsten, Marx, & York, 1999). Therefore, changes in the physical domain can add to the potential distress during this major life transition. A discontinuation of the rigorous training regimen that is a part of a college athlete’s daily life is almost certain to lead to changes in body composition and athletic abilities.

Aging. Along with drastic changes to exercise routines, the natural aging process inevitably produces bodily changes. Numerous studies have demonstrated the predictable increase in body fat mass and decrease in fat-free mass as one ages (Hughes, Frontera, Roubenoff, Evans, & Fiatarone-Singh, 2002; Gába & Přidalová, 2014). Further, as a result of these bodily changes, the aging adult is also likely to experience an overall decrease in physical function. Physical inactivity or a notable decrease in frequency and/or intensity of physical activity can often expedite these changes in body composition and function (Gába & Přidalová, 2014).

METHODS

The present study utilized a semi phenomenological descriptive research approach as a strategy for obtaining the most authentic information regarding this particular lived experience (Smith, Jarman, & Osborn, 1999; Yüksel & Yildrim, 2015). This study was guided by the following qualitative research questions:

1. What changes, if any, did former athletes recognize in their own body weight/image after their playing career ended?

2. What factors contributed to weight loss/gain and body composition changes in the 10+ years post-playing career?

3. What psychological factors contributed to the former athletes’ perception of their own body image?

Participants and Sampling

The population of interest for the study was retired female collegiate volleyball players. The sample consisted of 10 retired female volleyball players who formerly competed at a Division I university. Snowball sampling was utilized in the recruitment of participants. Inclusion criteria were based on length of retirement from collegiate sport (at least 10 years) and level of competition (participants must have competed at the Division I level). Potential participants were identified through contact with current and former collegiate volleyball coaches from within the intermountain west region of the United States.

Instrumentation

Interviews. A semi-structured interview protocol designed by the researcher was used to collect data. All interviews were conducted with each participant individually and were done over the telephone. This semi-structured format is the most widely used interview format in qualitative research (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006) and can generate reliable qualitative data (Cohen & Crabtree, 2006). Interview questions were open-ended and directly related to the study’s research questions. The telephone interviews lasted approximately 10 to 30 minutes, per participant. Only one researcher was responsible for conducting all of the interviews. This researcher asked each participant all of the pre-determined questions. The semi-structured nature of the interviews allowed for the researcher to make further inquiries concerning topics of interest. With participant consent, all interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Interview transcripts were sent to each participant for verification.

Demographic questionnaire. In addition to the interview session, each participant completed a short demographic questionnaire to gather basic descriptive information (e.g. age, current occupation, current level of physical activity). Some additional questions included in this questionnaire addressed participants’ sport experience (e.g. planned or unplanned retirement, age at the time of retirement).

Validity and reliability. To ensure validity of the instruments utilized in this study, two triangulation processes were carried out. First, member checking took place both during the interview and after the interview concluded. During the interview, the researcher restated or paraphrased the information provided by the participant and when necessary, asked the participant to repeat any phrases that were not clearly articulated. Following the interview, each participant was emailed a copy of the transcription of their interview, giving them the opportunity to make any corrections or further comments. The process of member checking has been identified as an effective strategy in qualitative research for increasing credibility (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Analyst triangulation was the second method of triangulation utilized in the study. Although only one researcher as responsible for conducting the interviews, multiple researchers were involved in the creation of the interview questions and data analysis.

Procedures

Following approval from the University’s Human Subject Committee, the researchers contacted personal acquaintances to conduct initial interviews. These personal acquaintances provided contact information for other potential participants. All participants were contacted via telephone. Before conducting the interview, the researcher outlined all of the information included in the statement of informed consent and did not proceed without receiving verbal consent from the participant. Sturges & Hanrahan (2004) found that telephone interviews yield comparable data and no significant differences in interview transcripts when compared to face-to-face interviews. Further, Novick (2008) suggests that telephone interviews might actually allow respondents to feel more comfortable with disclosing certain personal information. Although information can also be gained from a person’s body language, the absence of nonverbal data in telephone interviews is not necessarily a downfall of this interview method. The lack of nonverbal behaviors leaves no room for misinterpretation of these behaviors by the interviewer (Sturges & Hanrahan, 2004).

Data Analysis

To ensure the validity of the data, each interview was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim and then returned via email to each participant for verification. Following transcription and member checking, the qualitative data acquired from the interviews was reviewed by all of the researchers involved in the study. A thematic analysis of the interview content was then conducted. The researchers collaboratively generated initial codes and then identified major themes to describe the participants’ experience. Braun & Clark (2006) identify thematic analysis as a reliable, descriptive approach to qualitative data analysis that often produces unexpected insights. Further, thematic analysis is a relatively simple method of data analysis that is appropriate for use in wide range of qualitative research studies, including the study at hand (Braun & Clark, 2006).

RESULTS

Profile of the Participants

A total of 10 individuals were interviewed. All 10 participants also completed the demographic questionnaire and were interviewed by phone. Per the inclusion criteria, all participants were female and formerly played on a collegiate volleyball team at the Division I level. The demographic questionnaire provided researchers with further information regarding participants’ age, current occupation (sport-related or not), current physical activity level, and nature of their sport retirement (planned or unplanned). Ages ranged from 29 to 52 years of age. Half of the participants reported that their current occupation is volleyball-related (i.e. club, high school, or college volleyball coach). All participants reported being physically active; with the majority of participants reporting that they consistently engage in vigorous physical activity multiple times a week (e.g. running, biking, weight training, playing volleyball or tennis). Most participants’ retirement from sport was planned; three of the participants’ retirement was unplanned and due to a career-ending injury.

Thematic Constructs

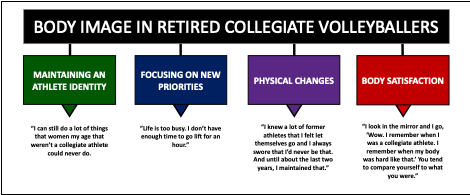

After manually coding the data, the researchers identified four themes: (a) maintaining their athlete identity, (b) focusing on new priorities, (c) physical changes, and (d) body satisfaction.

Figure 1. Body image in retired collegiate volleyball players: Thematic constructs.

Maintaining their athlete identity. All participants reported having acquired new professional and personal roles since their retirement from competitive sport, but each of them seemed to have maintained some degree of athletic identity. Some participants have taken up a new sport/sports since their retirement from collegiate athletics in order to stay active:

I quit playing volleyball but then I started playing rugby and then I started cycling… The last few years I’ve gotten really into mountain biking. (P9)

Participants also discussed their continued desire be involved in something competitive and often turned to other sports to satisfy that desire. Despite obvious physical deteriorations, the women still identified as an athlete, even though they were no longer competing collegiately:

I still can do a lot of things that most women my age that weren’t a collegiate athlete could never do. So, I feel like I have a lot of athletic ability, even though I’m a little older and slower. (P7)

P1 said it was hard to let go of the sport once her collegiate career ended, but discovered that just because her playing career ended, her affiliation with the sport did not have to:

I think it’s funny when you say, “after you were done playing.” I have to tell you, that’s why I still coach so much. I’m trying to transition my life. What happens if I don’t coach every day at 3 o’clock in the afternoon? And I’ve been doing this for 30 years. So, I don’t know that I’ve grown up and left the game. (P1)

Focusing on new priorities. Each participant discussed the acquisition of new professional and personal obligations since their playing career. Oftentimes, the women found professional workplace settings challenging, mostly because they involved being inactive for hours on end. The time commitment required by work responsibilities took precedence over maintaining a strict exercise regime:

When you’re playing collegiately, it’s like four hours of practice a day – including weights and things that you have to do. So, it’s hard to – I don’t think you can ever get back to that… Life is too busy. I don’t have enough time to go lift for an hour. (P10)

When I was a college athlete, basically I got paid to work out and be in shape. I mean, school was part of that, but there was a built in five to six days a week of fitness activities and now that’s not my job. So now it’s a matter of fitting it in around all my other work responsibilities and personal life responsibilities. (P2)

Motherhood was often cited as a priority that also detracted from a focus on physical health.

Before [having kids] you have tons of time and, you know, I played tons of tennis. I had lots of time to do all the right things for myself. But I think once you become a parent, that becomes a little more difficult. You have to balance more. (P7)

Physical changes. All but one of the participants reported experiencing noticeable physical changes including weight gain, loss of muscle mass, and chronic joint pain following the cessation of their collegiate athletic careers. Some attributed these changes partially or completely to pregnancy, motherhood or their role as a parent-figure. P5 told us she used to have an “athletic body” but now she had a “mom body,” P9 agreed that the demands of being a mother had forced her to put her own physical health and wellbeing aside. She explained, “I am probably larger, heavier, and the most out of shape now than I’ve ever been in my life. (P9). Motherhood was not the only reason cited for physical changes. Others felt the changes were just part of natural aging process:

I definitely have seen changes in my body since I’ve not been playing college volleyball. However, it was slow to happen. It was more of an aging process that I noticed through the years. (P1)

I’ve put on some weight… I’m definitely not as fit, but I mean, at fifty-two you’re not going to be [what you were at] twenty years old. (P7)

Many participants explained that the physical changes they’ve experienced were unanticipated, and not something that they ever thought about during their time as a college athlete:

You don’t even think about those things. You just take it all for granted and you know, you feel like you’re fit and you’re going to be young forever and you’re going to be able to do everything. (P7)

Others did anticipate that certain physical changes would occur after their playing career. A number of participants said this was because they had seen older teammates in their retirement that had not maintained their level of fitness:

I knew a lot of former athletes that I felt let themselves go and I always swore that I’d never be that. And until about the last two years, I maintained that. (P9)

I had a lot of older teammates so I kind of watched them go through the process in years before I did. So, I knew [my body] would change and I knew some teammates who stayed active and others who didn’t. It was something I could acknowledge was going to happen. (P2)

Body satisfaction. Most participants reported a change in their body satisfaction and body esteem as they began to experience physical changes following their sport retirement. The direction of that change, however, was inconsistent. Some participants reported what could be interpreted as a negative change:

Depressing is a strong word, but it was just kind of like, ‘Oh, man!’ Here I was at the top of my game, at the top of the collegiate level… Then you get married and have kids and your body – mentally you’re just not where you used to be. (P5)

[When] I was an athlete and I was in good shape… I had less concern over body image or what I looked like or how clothes fit. That’s definitely something I consider more now. (P2)

Some recounted situations from their playing careers, like being monitored by weigh ins, that have led to a more negative body image:

It was more about how we looked and we had to lose weight. You always had to be thin. It wasn’t about being a strong woman. So, I think that does affect the people that have been through that era. It wasn’t pretty to be a muscular woman then. (P1)

A number of participants talked about often comparing their current physical condition to what it was during their time as a college athlete. One participant discussed how still being involved with the sport as a coach might influence the tendency to make those kinds of comparisons:

Of course! I look in the mirror and I go, ‘Wow. I remember when I was a collegiate athlete. I remember when my body was hard like that.’ You tend to compare yourself to what you were… I’m surrounded by collegiate athletes and 18-year-old girls. I see where they are in their prime, so I’m continually reminded of that. I’ll look at a kid and be like, ‘I remember when I was like that.’ (P1)

Only one participant reported developing a more positive body image.

In college you’re a little more self-centered, I guess. I was more insecure about my body even though I look back and was in – I looked great! Now, I still work on being fit and want to physically look good, but I realized that’s not the most important thing. I’m more accepting of who I am… I feel more confident in who I am now. Even though I may not be as physically – or visibly fit as I was then. That’s just part of getting older I think. (P6)

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the body image of former Division I female volleyball players. There were a few notable limitations to the study. First, the researchers used snowball sampling as a recruitment technique, beginning with a convenient sample of former collegiate volleyball players who lived in close proximity of the researcher. Those individuals that chose to participate may have had personal interest in and/or experience with the subject matter being investigated. While this does not warrant dismissal of the results, it does potentially bias the results. Further, the generalizability of the results is also limited, however that is often the case with qualitative research (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Neither of these limitations discredit our findings.

While former collegiate volleyball players may experience some difficulty related to body image following their sport retirement, these difficulties are not particularly severe, especially when compared to other athlete populations (Stephan, 2010; Stephan & Bilard, 2003; Warriner & Lavalee, 2010). In exploring the construct of body image, three other major themes emerged from the qualitative data collected: always an athlete, new priorities, and physical changes. These four interconnected themes each play a notable role in the retirement experiences of all 10 participants interviewed.

Maintaining Their Athlete Identity

Most participants seemed to have maintained their athletic identity to some degree. Many discussed their current physical competencies and competitive drive and all participants reported being either active or very active on a regular basis. Most have taken up a competitive sport, like tennis or cycling, to satisfy their competitive drive and remain active. Prior research has found that failure to fully disengage from the athlete role can result in identity confusion and can intensify the difficulty experienced during sport retirement (Lavallee, Gordon & Grove, 1997; Warriner & Lavallee, 2010). However, it seems that among the participants in this study, maintaining some degree of athletic identity has acted as a protective factor, allowing the former athletes to preserve their sense of athletic competence and desire to be active. Unlike other athlete groups (e.g. elite female gymnasts, Olympic athletes) studied in similar research, none of these former volleyball players formed an exclusive athletic identity during their playing career (Stephan & Bilard, 2003; Warriner & Lavallee, 2010). This is likely due to the nature of college athletics versus the nature of professional/Olympic level sport participation. The participants in the present study were able to explore and identify with other roles during their time as college athletes and for most, graduation from college marked the foreseeable conclusion of their career as competitive volleyball players. Only one participant’s playing career continued to the professional level. It is interesting, but not surprising, to note that this participant seemed to have maintained a greater degree of athletic identity than the others. She reported that 30 years into her retirement, she still “has not grown up and left the game”.

Focusing on New Priorities

Only one participant in the present study advanced to the professional level following her collegiate playing career. This is a fairly accurate representation the fate of the college athlete population as a whole – only about 3% of all college athletes will continue their playing careers after college (NCAA, 2016). The majority of college athletes will experience a shift in priorities and responsibilities upon graduation from college and retirement from competitive sport. This was something that the participants in the present study spent a significant amount of time discussing in their interviews. Since their sport retirement, all of the participants had entered the workforce; most also married and had children. For many, taking on new responsibilities in life allowed for a smooth transition out of sport and into new roles. As discussed above, none of these former athletes developed an identity exclusive to their athlete role, making the exploration and acquisition of new roles easier than it might be for other athlete populations. However, new personal and professional responsibilities meant less time for physical activity. Many of the participants explained that as a college athlete they spent a large part of each day training or competing. In their current life situation, dedicating that much time to physical activity would be impossible.

Physical Changes

All but one former athlete interviewed reported experiencing physical changes during their sport retirement. Weight gain, loss of muscle mass, and chronic joint pain were the most commonly reported changes. Physical changes are to be expected when the frequency, intensity, and type of exercise changes (Gába & Přidalová, 2014). Many of the participants attributed their weight gain and loss of muscle mass specifically to the adoption of a less frequent and less intense exercise regime. The participants older in age all seemed aware of the inevitability for certain change to occur during the natural aging process and made mention of this while discussing the changes they have experienced. Others spoke of pregnancy and the changes they saw and felt in their bodies after having children.

In contrast to other retired athlete populations, physical changes did not seem to produce a significant amount of distress in any of the former athletes who were interviewed in the present study (Stephan & Bilard, 2003; Warriner & Lavallee, 2010). Former athletes who encounter significant difficulty in accepting changes such as weight gain, loss of muscle mass and degradation of physical competencies tend to have a more exclusive athletic identity and often derive much of their self-worth from their sport-specific competencies and athletic body (Warriner & Lavallee, 2010; Stephan & Billard, 2003). The absence of exclusive athletic identity amongst all participants in this study likely played into their ability to accept the changes experienced, even if those changes were not positively perceived.

Body Satisfaction

All participants reported some change in their body image since their time as collegiate athletes. However, the direction of that change varied among participants. One participant reported a positive change in body image, as the result of diminished concern over physical appearance and improvement in self-confidence. Others reported very little change in their body image and body satisfaction over time. A number of the former athletes reported comparing their current physical appearance and fitness to what it once was, which at times, led to temporary body dissatisfaction and somewhat negative body image. Making comparisons between current and former physical fitness was most commonly reported among participants who have remained involved with the sport as high school, college or club volleyball coaches. Being surrounded daily by young athletes, who are likely at or near the peak of their sport performance and overall physical fitness, may not be an environment conducive to body satisfaction and positive body image for some former athletes.

Conclusion

While there is an abundance of research available on the way current collegiate athletes view their bodies, there has been a dearth of research targeting those same athletes years after their playing careers have ended. Taken together with previous research, the findings of this study may help to illustrate some of the physical and psychological issues that are experienced by former female collegiate athletes. Athletes may be unique in the way they perceive aging. Previous research has suggested that the means by which older women evaluate their bodies shifts from appearance to physical function (Franzoi & Koehler, 1998). Appearance has also been shown to be a very important issue for older women (Slevin, 2010). For a former college athlete, this view may be intensified. Further study directing comparisons between the populations is warranted. Future research might also consider other retired athlete populations such as former male athletes or retired female athletes who participated in a different sport.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Feeding and eating disorders. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/documents/eating%20disorders%20fact%20sheet.pdf

Beamon, K. (2012). “I’m a baller”: Athletic identity foreclosure among African-American former student-athletes. Journal of African American Studies, 16(2), 195-208. doi: 10.1007/s12111-012-9211-8

Bjornsson, A.S., Didie, E.R., & Phillips, K.A. (2010). Body dysmorphic disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(2), 221-232.

Braun, V., & Clark, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101

Brewer, B.W., Van Raalte, J.L., & Linder, D.E. (1993). Athletic Identity: Hercules’ muscles or Achilles heel? International Journal of Sport Psychology, 24(2), 237-254.

Campbell, A., & Hausenblas, H.A. (2009). Effects of exercise interventions on body image: A meta-analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(6), 780-793. doi: 10.1177/1359105309338977

Cash, T.F., & Fleming, E.C. (2002). The impact of body image experiences: Development of the Body Image Quality of Life Inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31(4), 455-460. doi: 10.1002/eat.10033

Cohen, D. & Crabtree, B. (2006). Qualitative research guidelines project. Retrieved from http://qualres.org/HomeSemi-3629.html

Creswell, J.W. & Miller, D.L. (2000). Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124-130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

DiCicco-Bloom, B. & Crabtree, B.F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40, 314-321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

Flament, M.F., Hill, E.M., Buckholz, A., Henderson, K., & Tasca, G.A. (2012). Internalization of the thin and muscular body ideal and disordered eating in adolescence: The mediation effects on body esteem. Body Image, 9(1), 68-75.

Fortes, L.S., Neves, C.M., Filgueiras, J.F., Almeida, S.S., & Ferreira, M.E.C. (2013). Body dissatisfaction, psychological commitment to exercise and eating behavior in young athletes from aesthetic sports. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano, 15(6), 695-704.

Fortes, L.S., Paes, S.T., Neves, C.M., Meireles, J., & Ferreira, M.E.C. (2015). A comparison of the media-ideal and athletic internalization between young female gymnasts and track and field sprinters. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 9, 282-291.

Franzoi, S. L., & Koehler, V. (1998). Age and gender differences in body attitudes: A comparison of young and elderly adults. International Journal of Human Development, 47(1), 1–10.

Fuller, R.D. (2014). Transition experiences out of intercollegiate athletics: A meta-synthesis. The Qualitative Report, 19(46), 1-15. Retrieved from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss46/1/

Gába, A., & Přidalová, M. (2014). Age-related changes in body composition in a sample of Czech women aged 18-89 years: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Nutrition, 53(1), 167-176. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0514-x

Grabe, S., Ward, L.M, & Hyde, J.S. (2008). The role of media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460-476.

Greenleaf, C., Petrie, T.A., Carter, J., & Reel, J.J. (2009). Female collegiate athletes: Prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors. Journal of American College Health, 57, 489 – 495.

Haase, A.M. (2011). Weight perception in female athletes: Associations with disordered eating correlates and behavior. Eating Behaviors, 12(1), 64-67.

Hausenblas, H., & Downs, D.S. (2001). Comparison of body image between athletes and nonathletes: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 13(3), 323-339. doi: 10.1080/104132001753144437

Hughes, V.A., Frontera, W.R., Roubenoff, R., Evans, W.J., & Fiatarone-Singh, M.A. (2002). Longitudinal changes in body composition in older men and women: Role of body weight change and physical activity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(2), 473-481

Josephs, R. (2006, January). Time to be candid about 20-hour rule. NCAA News Archive. Retrieved from http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/NCAANewsArchive/2006/Editorial/time+to+be+candid+about+20-hour+rule+-+1-2-06+ncaa+news.html

Lavallee, D., Gordon, S., & Grove, J.R. (1997). Retirement from sport and the loss of athletic identity. Journal of Personal and Interpersonal Loss, 2, 129-147. Retrieved from http://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/7654/1/JPIL_1997.pdf

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Mazić, S., Lazović, B., Delić, M., Suzić Lazić, J., Aćimović, T., & Brkić, P. (2014). Body composition assessment in athletes: A systematic review. Medicinski Pregled, 67(7-8), 255-260. doi: 10.2298/MPNS1408255M

Muscat, A.C., & Long, B.C. (2008). Critical comments about body shape and weight: Disordered eating of female athletes and sport participants. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(1), 1-24. doi: 10.1080/10413200701784833

National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). (2008). CHAMPS/Life Skills Program 2008-09. [Brochure]. Indianapolis, IN.

North, J. & Lavallee, D. (2004). An investigation of potential users of career transition services in the United Kingdom. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(1), 77-84. doi: 10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00051-1

Novick, G. (2008). Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Research in Nursing & Health, 31, 391-398.

Rodgers, R., Cabrol, H., & Paxton, S.J. (2011). An exploration of the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among Australian and French college women. Body Image, 8(3), 208-215.

Saint-Phard, D., Van Dorsten, B., Marx, R.G. & York, K.A. (1999). Self-perception in elite collegiate female gymnasts, cross-country runners, and track-and-field athletes. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 74, 770-774. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Brent_Van_Dorsten/publication/12827391_Self-perception_in_elite_collegiate_female_gymnasts_cross-country_runners_and_track-and-field_athletes/links/09e4150a6d60306030000000.pdf

Slevin, K. F. (2010). If I had lots of money…I’d have a body makeover. Managing the aging body. Social Forces, 88(3), 1003–1020.

Smith, J.A., Jarman, M., & Osborn, M. (1999). Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Health Psychology, 218-240.

Smolak, L., Murnen, S., & Ruble, A. (2000). Female athletes and eating problems: As meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 27(4), 371-380.

Stephan, Y., Bilard, J., Ninot, G., & Delignières, D. (2003). Repercussions of transition out of elite sport on subjective well-being: A one-year study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15(4), 354-371. doi:10.1080/714044202

Stephan, Y., Torregrosa, M., & Sanchez, X. (2006). The body matters: Psychosocial impact of retiring from elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(2007), 73-83. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.01.006

Stice, E., & Bearman, S.K. (2001). Body-image disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: a growth curve analysis. Developmental Psychology, 37(5), 597-607.

Sturges, J.E., & Hanrahan, K.J. (2004). Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qualitative Research, 4, 107-118.

Sundogt-Borgen, J., & Torstveit, M.K. (2003). Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, 14(1), 25-32.

Thompson, J.K., Heinberg, L.J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Varnes, J.R., Stellefson, M.L., Janelle, C.M., Dorman, S.M., Dodd, V., & Miller, M.D. (2013). A systematic review of studies comparing body image concerns among female college athletes and non-athletes, 1997-2012. Body Image, 10(4), 421-432.

Warriner, K. & Lavallee, D. (2008). The retirement experiences of elite female gymnasts: Self-identity and the physical self. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(3), 301-317. doi: 10.1080/10413200801998564

Yüksel, P. & Yildrim, S. (2015). Theoretical frameworks, methods, and procedures for conducting phenomenological studies in educational settings. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 6(1), 1-17. doi: 10.17569/tojqi.59813