Our framework for this project was also influenced by the

work of Albert Bandura as ELT bears some similarity to Bandura’s Social

Learning Theory (SLT). Of interest for this study, Bandura (1986) suggested

that learning was a cognitive process that took place in a social context.

Bandura (1986) stressed the importance of observing, modeling, and imitating

the behaviors and actions of others. Positive and negative reinforcement (which

can also be external or internal) of learned behaviors and actions is also

important to the learning process. Bandura (1977; 1986; 1997) repeatedly found

a student will replicate actions or behavior they believed would lead to a

positive response. However, the response would not matter to the student unless

it matched the student’s individual interests and needs. Lave & Wenger (1991)

used SLT to challenge the notion that learning is simply the reception of

factual knowledge or information. Instead, they contended that students learn

best by being part of a team that actively engages in practice rather than by

memorization. Central to SLT is the belief that “a person’s intentions to learn

are engaged and the meaning of learning is configured through the process of

becoming a full participant in sociocultural practice” (Lave & Wenger,

1991, p. 27)

The context described by Bandura (and subsequently by Lave

and Wenger) has key similarities to Kolb’s learning cycle. First, both theories

call for students to learn by doing. Second, both ELT and SLT stress the

importance of students being able to recall and apply classroom concepts to real

workplace scenarios. Third, both theories cite the value of student reflection

(Bandura, 1997) as a key component of learning. Therefore, an understanding of

the role of reflection is informs our work as well. Jerome Bruner (1960) added

that reflection “is central to all learning” (p. 13) and that the range of

reflection varies from the simple to the complex. Experiential learning

provides opportunities across the learning cycle to reflect on learning as

something of meaning that can then be carried across time, even as new

information or perceptions shape one’s future understanding of what is known

(Pauline, 2013).

Purpose Statement

We believe that experiential learning can transform the

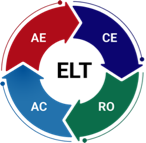

learning process (Kurt, 2020; Kolb, 2015). Thus, the purpose of this paper is

to describe how a week-long capstone experience at a NCAA championship event,

the 2021 Big Sky Conference’s Men’s and Women’s Basketball Tournaments, helped

to produce optimal learning outcomes for a group of undergraduate sport

management students. Using Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) as a

framework for understanding, we aim to show how our students benefitted in

multiple ways: through the contextual application of existing knowledge,

through the acquisition of new knowledge, by experimenting with new knowledge,

and from a unique opportunity for professional networking.

METHODS

Participants and Sampling

As in previous years, senior sport management students from

Idaho State University were invited to take part. Because of the ongoing pandemic,

restrictive attendance guidelines, and the need to implement additional

physical distancing precautions, only 10 students were allowed to participate

in 2021. Students were selected based on (a) their academic status as a senior

in the undergraduate SMP at ISU, (b) the students’ career interest to work in

collegiate athletics, (c) faculty recommendation, and (d) the students’

availability to travel to the event location (approximately 250 miles from our

campus) and work throughout the entire week. Selecting students who had already

fulfilled a majority of their course curricula was key to ensure students had a

solid theoretical foundation in sport management.

Procedures

As Team Liaisons, our students were tasked with

serving as team hosts, assisting with risk management and in-game marketing and

promotions, and media relations. Instructionally, we used our Sport

Facilities and Event Management class (a senior-level class) to prepare the

students for this experience. Job descriptions already existed, but they

did need to be tweaked for 2021. We knew it would be particularly challenging

given the fluidity of COVID-19 and the NCAA’s guidelines on creating a safe

sport environment amidst the global pandemic. The DC worked closely with his

supervisors to create a plan to use our students. That plan adhered to both the

NCAA’s guidelines and those recommendations set forth by the BSC’s Health

and Safety Committee. Ticket sales at the tournaments were limited to only

parents or direct family members of participating student-athletes. Therefore,

some job duties that our students had previously performed, like those related

to external marketing and fan engagement, were eliminated. The students

inherited other tasks, like cleaning and disinfecting team areas. Because our

participation number was forced to be smaller in 2021, our students would be

challenged on some job assignments (like ushering teams and managing post-game

press conferences) to work independently rather than in pairs or small groups

like they had been able to do in years past.

To combat role ambiguity, training for our students began six

weeks prior to the actual event. When possible, we contextualized textbook

readings and classroom discussion in the Sport Facilities and Event

Management class by relating it to NCAA tournament operations. For example,

in class we reviewed the importance of sponsorships. Learning objectives called

for the students to be able to define and distinguish between different levels

of sponsorship, determine what a good sponsorship fit might be, write sponsorship

proposal letters, and create a sponsorship agreement. While our students’

assignments were simply for practice, we used the tournaments as a catalyst.

The lessons culminated when BSC administrators shared insight about their

process of securing sponsorships for the basketball tournaments. They even

shared their actual sponsorship agreements with our students. We also invited

the marketing director of the tournament’s title sponsor to address the class

and explain to them what his organization was hoping to gain from the

partnership. While in Boise, our students were able to witness the activation

strategies.

Three weeks prior to the tournaments, five junior and senior

administrators at the BSC, including the DC and Senior Woman Administrator,

joined our class via Zoom. The goal of this videoconference was to

introduce the students to the organizational hierarchy of the BSC and to

familiarize the students with the job duties of each professional. Students

were provided with a brief history of the BSC, its role in the NCAA governance

process, information relative to the conference championship site selection

process (including how Boise was selected as the host site for basketball), and

logistics surrounding championship operations (e.g., venue selection and

preparation). We provided the students with a Team Liaison Manual.

Students were assigned to review the manual in preparation for their jobs in

Boise. Two weeks prior to our trip, the DC hosted a mandatory in-service for

our students. He reviewed, in detail, the students’ job descriptions and the

specific duties they would be expected to perform. Items such as appropriate

dress, time demands, behavioral expectations and COVID-19 protocols were also

addressed. The in-service lasted two hours. A week prior to departure, students

were provided their hotel and room assignments. Students were expected to

arrive in Boise, the tournaments’ site, by noon on Sunday, the day before the

women’s tournament started, to assist with court and facility setup and facility/community

branding. They were required to test negative for COVID-19 prior to departure.

Over the course of the seven consecutive days our students

were in Boise, they assisted with the management of 20 games. On average, each

student worked 12-hour days. Because the men’s and women’s tournaments took

place at the same facility, a single day’s work schedule was as long as 18

hours, with as many as six games taking place on a single day. Like other sport

managers across the NCAA, our students were charged with taking proactive

measures to mitigate the impact and spread of the spread of the COVID-19 virus.

The BSC designated our students as Tier Two staff members (a NCAA

designation), meaning they would come in close contact with Tier One

individuals (players, coaches and select administrators) and would be expected

to maintain reasonable physical distance and wear face coverings at all times.

Like the participating student-athletes and coaches, our students were tested

daily for the COVID-19 virus. If a student were to test positive (none did),

he/she would be quarantined in a separate hotel room until he/she was able to

return home. At the conclusion of each workday, the DC huddled with the

students collectively to review discuss any incidents or problems that may have

occurred and offer the students’ guidance. Students were also given their job

assignments for the next day.

While we, as faculty, attended the tournaments with our

students in 2019 and 2020 in a supervisory role, we were unable to attend in

2021 due to pandemic-related restrictions. The students knew the DC was their boss

for the week and they were responsible for reporting directly to him. We

communicated daily with our students and with the DC by phone and by email to

ensure the students were meeting expectations. We also relied on one of our

graduate students in Athletic Administration to supervise the students’

behavior in our absence. She had previously participated in the experience as

an undergraduate student and was completing a semester-long internship with the

BSC, so we were comfortable with her in that leadership role.

Because of limited resources caused by the pandemic

(including loss of revenue caused by pandemic-related restrictions on ticket

sales at the tournaments), the BSC was unable to provide the amount of funding

we received the first two years of our involvement. The Dean of our College of

Education (COE) felt the educational value of the experience warranted the

additional expense and she agreed the COE would cover approximately 70% of the

hotel costs. The BSC was able to cover the remaining amount, and they again

provided the students with their meals and with BSC-branded apparel.

Data Collection

Reflective practice allows experience to be converted into

learning (Dewey, 1933; Knowles et al., 2014). It can help students become more

self-aware and feel more comfortable addressing challenging situations

(Anderson et al., 2004). Pauline (2013) also asserted the value of reflective

assignments into the experiential learning process. She stated the “students

developed the ability to progress from ‘noticing’ or ‘making sense’ to ‘making

meaning’ from their experiences” (p. 10). Tacit knowledge, or that which a

student learns through experience rather than traditional academic means

delivered in the classroom setting, is bettered by reflective activities

because it can help students alter future behavior (Cropley et al., 2010).

During the week of the tournaments, we asked our sport

management students (SMS) to journal about their experiences. Additionally,

after the tournaments ended, we asked them to complete a survey as an

additional way to reflect upon their experiences. In the survey, we asked our

students to summarize, (a) what they learned from engaging in the experience, (b)

how their sport management/athletic administration courses had prepared them

for the experience, (c) any challenges they encountered, (d) the opportunity

they had for professional networking, and (e) if and how the experience

reinforced their desire to work in the sport management industry. Additionally,

we sought feedback from the BSC administrators who supervised our students at

the event. We wanted to know how well the students performed their job duties,

the value of their contribution in terms of the overall success of the

championship event, and we wanted to know their thoughts on how we, as faculty,

could improve our preparation of students who choose to engage in the

experience in the future.

Data Analysis

Because our approach to this study was qualitative, we used a

process of open coding to reduce the amount of data we acquired through the

students’ reflections and from the post-event survey (Sang & Sitko, 2015).

Open coding has been described by Strauss and Corbin (1990) as a necessary first

step. Hence, our goal here was to sift through the dozens of pages of raw data

we had obtained and condense it into manageable chunks of useful information.

We followed up the open coding process with axial coding. Axial coding calls

for researchers to investigate the relationships that exist amongst concepts

and categories (Denzin & Lincoln, 1998; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss

& Corbin, 1990;). To do this, we grouped our students’ responses according

to their applicability to three pre-determined (a priori) themes consistent

with Kolb’s theory: (a) contextual application of existing knowledge, (b)

acquisition of new knowledge, and (c) experimenting with new knowledge. A

fourth theme, (c) professional networking, was added a posteriori. While it may

not be directly related to Kolb’s work, socialization and networking has been

noted by many other scholars as a significant benefit of experiential learning

(Bandura, 1997; Deluca & Fornatora, 2020; Odio et al., 2014; Sattler &

Aichen, 2021). As we read (and re-read) the students’ reflections and

responses, we highlighted remarks we felt provided evidence of each of those

themes. Biddle, Markland, Gilbourne, Chatzisarantis, and Sparks (2001)

suggested that readers be provided with an opportunity to evaluate and interpret

interview data in a way that is most meaningful to them. Therefore, the

findings of this study are presented using direct quotations and are parsed

using theoretical descriptions of each theme.

RESULTS

Contextual Application of Existing Knowledge

Kolb (1984) believed that a person could not learn simply by

observing or reading. Instead, the person must be fully engrossed in the

activity as a hands-on participant. This is the crux of Kolb’s Concrete

Experience (CE) stage. Kolb (1984) said that in order to maximize the

effectiveness of the Concrete Experience stage, students must be able to

involve themselves fully, openly, and without bias in new experiences. Harris

(2019) added the importance of contextually rich concrete experiences.

He wrote, “experiential learning is conceptualized by educators and scholars as

a process in which learners are immersed in learning experiences that contain

the fullest contextual information possible” (p. 1066).

Our students learned about their job expectations before going

to Boise, and once at the venue, they demonstrated their readiness. When they

arrived at the venue a day prior to the start of the tournaments, they were

issued work credentials and then given a tour of the facility so that they

could orient to the layout. After this brief orientation, our students helped

to transform the venue into a basketball facility (it is typically used for

hockey during winter months) by “setting up and putting down court tape”

(SMS-2), organizing the locker rooms and team rooms, sectioning off spectator

areas for each team, and preparing tournament pass lists.

Experiential learning works best when it provides students

with the opportunity to apply what they know (Kolb, 1984; Kurt, 2020).

Throughout the week, ours were expected to use their Sports Law class

training to “identify and minimize any potential risks” (SMS-9) at the venue.

Duties ranged from clearing court debris, such as wiping up any wet spots or

moisture on the court or sweeping the court floor, to locker room and courtside

security. One student understood the magnitude of his responsibility saying,

“we worked as a team to provide the highest level of safety for staff,

athletes, and coaches” (SMS-3). Content taught in our SMP’s Sport Marketing

class also was recognized. Students noted their duties to help brand the courts

with BSC and sponsor logos (SMS-1; SMS-2; SMS-4; SMS-6: SMS-8). Theming the

arena as a championship venue had a notable impact on the students. The BSC

even provided each student with Big Sky-branded apparel to wear each day. This

was especially exciting for our students as it reinforced their role as members

of the BSC’s team (not as students). Our students also reported being actively

involved with “helping with in-game promotions” (SMS-2), with “writing game

scripts” (SMS-7), and by “putting signs up around town” (SMS-4). They also

practiced customer service, meeting and escorting teams to their locker rooms

or team area once they arrived at the facility. Team liaisons continued to

serve as the primary point of contact for each school’s Director of Basketball

Operations throughout the week, to assist with any team needs that arose. Our

students took initiative to implement green strategies, too, by setting up

recycling stations for disposal of plastic bottles.

Because of COVID-19, the need for regular and prompt cleaning

and disinfecting of surfaces was critical. It was a duty charged to our

students, and they understood its importance and its relevance to overall risk

management. They also understood the importance of their jobs in relation to

the flow of the overall event, like sanitizing the fan seating areas before and

after each game. SMS-7 acknowledged, “It was important that I had everything on

my end completed in a timely manner because I had other people relying on me to

do so.”

Often, our students described some of their jobs as “little”

(SMS-1; SMS-2; SMS-3; SMS-4; SMS-8), but that did not mean our students viewed

them as unimportant. SMS-5 stressed this saying, “every role you play in an event

is valuable.” Others agreed. SMS-3 addressed the importance of the “little

things:”

I loved being able

to pay attention to details of wiping off the backboards, putting the spotlight

on the players during the player introductions, getting the players to the

locker rooms and filling up the fridges with Gatorades. They may be little

things, but I saw that they are important things. It all just made me

appreciate this industry.

SMS-4 was impressed with the variety of work he was asked to

do and how that work contributed to the overall success of the tournaments:

We learned a lot

about the little tasks that need to be done at the tournament. I had several

different roles [throughout the week: team liaison, ball person, stats

assistant, stats runner, and I even helped with ticketing. We helped stock

fridges and set up signage . . . . As a stats assistant and stats runner, I was

able to learn more about the analysis of a game. There were a ton of little

details that helped make the tournament so great and flow smoothly.

Experiential learning bridges the gap between theory and

practice (Bower, 2013; Diacin, 2018). Our students were able to see first-hand

how their curriculum prepared them to be sport managers. Students commented

most on the practical application of information they acquired in their Sport

Facility and Event Management course.

This experience

really helped me to understand what we talked about in the classroom. For

example, in my Facilities class last week, we were talking about organizational

culture and job stress. Even though I was only a part of the Big Sky team for a

week as a nonstandard worker, they made me feel like I was an important part.

We learned in class that you need to really appreciate your volunteers. I was

always treated with respect. They seemed genuinely thankful for the work I did.

I felt like a part of the team. (SMS-5)

Within Kolb’s Reflective Observation (RO) stage,

students are allowed to note any inconsistencies between experiences and

understanding (Kolb, 1984; McLeod, 2017;). The goal of this stage is for the

student to recognize any inconsistencies that might exist in their knowledge

and the experience and to personally review those situations and find meaning.

Sato and Laughlin (2018) summarized the process of learning and the value of

reflection in that process:

Foundational

experiences provide opportunities for observation and reflection. Reflection

leads to new ideas or modification of old ideas. Changing ideas lead to new

implications and form the basis for experimentation. The process of actively

testing ideas through experimentation creates new experiences and the cycle

continues. Ultimately, the continual process of experience, reflection,

thought, and action creates new knowledge.

Our students were able to apply existing knowledge, but they

also saw the value in how that application could lead to more knowledge. SMS-1

wrote, “I learned so much this week. I learned that a lot more things go on

behind the scenes than what I originally thought.” SMS-3 said he had worked at

“a lot” of sport events previously and even completed a 135-hour internship in

a Division I athletic department, but that those experiences paled in

comparison to the immersive experience he received in Boise. He wrote about

being involved in “every aspect” of tournament management and seeing things

from “a totally different perspective.” He said the week-long experience

reaffirmed his career choice. Summarizing the experience, he reflected, “I

learned that I absolutely love college athletics. I have seen that from my

other internship experiences, but this was my first opportunity to [work in]

college athletics for 7 straight days for 15-18 hours a day.”

Acquisition of New Knowledge

Within the Abstract Conceptualization (AC) stage,

“reflection gives rise to a new idea, or a modification of an existing abstract

concept” (McLeod, 2017). In this stage, the learner develops theories to

explain their experiences. Recurring themes and problems give birth to new

ideas and new solutions. SMS-7 understood the value of not always following a

template. He wrote, “when you are in the thick of it you get to learn from

trial and error.” SMS-3 was another who recognized how he had developed

additional preparedness:

As great as learning

in a classroom is, I have learned that it is difficult to know exactly how

everything in [managing] athletics until you are participating in it. I was

able to see why communication skills were so important between both the

marketing side of things with fans, as well as with our interactions between

staff and players. I was also able to see how important getting facilities

ready and putting everything in the right place. I recognized how important

good organizational management skills were as well, as everyone around was able

to instruct us effectively and allowed to gain as much experience as possible

with the tasks at hand. (SMS-3)

Deluca and Fornatora (2020) studied experiential learning in

relation to the perceptions of students. They found the experiences to be “eye

opening” (p. 146) because they were exposed to areas they previously had not

considered. Though they knew in advance what their work expectations would be,

our students were not prepared for the physical and mental exhaustion they

would experience. With 20 games spread across six days, the students

experienced “long days and sleepless nights” (SMS-4). After one 16-hour day,

SMS-7 wrote that he was proud of himself and his classmates because even with

16-hour workdays, they had “worked tirelessly to get everything done that

needed to get done” that day. At the end of the week and feeling “exhausted,”

SMS-2 said by working so many hours, she realized “burnout in this industry is

real.” SMS-3 said he learned to cope with his exhaustion by “mak[ing] sure that

I did everything I could to stay involved in the day and never think about how

long I had worked, but rather look forward to the next task that I could be a

part of.” SMS-5 had her own way of dealing with the long days. She wrote,

In the middle [of

the week] when we had long days, I felt like I had moments of growth where I

was exhausted and at times having a hard time dealing with my peers just

because we had been together so much, but I was able to bring it back in and

look at the bright side.

Physical exhaustion was experienced by many of our students,

result for many, but the excitement of the opportunity still trumped being

tired:

Normally I do not

even look forward to an 8-hour workday with whatever job I do and that is with

getting paid as well, this was unpaid, and we worked ridiculously long days, my

feet were sore, and I loved every second I got to be a part of it. (SMS-3)

Experimenting with New Knowledge

Within Kolb’s Active Experimentation (AE) stage,

the student applies their ideas to the world around them to see what happens

(Kolb, 1984; McLeod, 2017). It is in this stage that learners take risks and

implement their theories. By doing so, they find new ways to improve their

skills and knowledge base. SMS-10 acknowledged that he “learned how to think on

[his] feet and problem solve on how to provide a better experience for coaches

and student-athletes.” Bandura (1997) advised that students who have

opportunities to engage in applied learning or problem-solving in their

university education may develop increased levels of self-efficacy, too. This,

in turn, can lead to increased motivation. SMS-6 said she had to be a “ready learner”

with every task she was given. A couple of our students commented on not having

a significant amount of experience with the sport of basketball, in particular.

They admitted to being “a little uncomfortable at first” (SMS-2) assisting with

game statistics or acting as the officials’ time out coordinator but that

“everyone helped [him] figure out how to do those positions” (SMS-5). A student

assisting with in-game promotions recalled, “with a lot of giveaways available,

I had to be very strategic on how to give them away . . . but I was able to

find a way to do this, and it created an even more fun fan environment towards

the end of the week” (SMS-7). COVID-19 protocols were established, but the

fluidity of various circumstances necessitated adaptations, at times. When one

winning team did not vacate their locker room on schedule after their game, it

resulted in that team missing its scheduled COVID testing time. Ensuring the

teams were escorted to the test location on time was one of our students’ obligations.

Reacting to the situation, SMS-9 said he had to react quickly with a solution

so that two teams “didn’t run into each other at testing.” He said he

communicated by radio with a test site coordinator and elected to stage the

team in an adjacent room until the test site was cleared.

Dealing with human emotion was an unexpected challenge for

several of our students. SMS-9 explained that towards the end of the men’s

tournament, “we had some players and coaches break down and I found it hard to

communicate at times with them.” SMS-6 added, “I found it challenging when I

would see athletes and coaches crying after their losses. As a neutral party, I

did not really know how to help or if I really could.” One of our student’s

jobs was to find and escort coaches and specific players to media room

immediately after games. This particular student also had to ensure locker

rooms were cleared quickly so that they could be cleaned for the next team

coming in. SMS-4 wrote about a particularly challenging situation he

encountered:

One of the last few

games a student athlete had a mentally tough time and we could hear screaming

and punching of walls in the locker room. This athlete and basketball staff

were emotional, and I did not know how to handle the situation at first but

then I assessed the situation and came up with a plan and was able to be a part

of de-escalating the situation and get the team and coaches where they needed

to be.

Some students said they got emotionally invested, too. SMS-5

said watching the “highs and lows of teams” made being a team liaison “more

than a job.” Others agreed. Several cited the thrill of watching the respective

champions cut down the nets as a highlight. “Knowing we played a part in that,”

SMS-8 said, “made it feel like we had won, too.”

Professional Networking

Bandura (1997) suggested that learning was a cognitive

process that took place in a social context. Additionally, relationship

building is a key outcome of experiential learning (Deluca & Fornatora,

2020). Gauthier (2018) also encouraged college sport management students to

seek volunteer opportunities and to build professional networks.

Our students were given an unprecedented opportunity to

network with industry professionals from eight western states. The opportunity

was not lost on our students. Each of them wrote about their networking

experiences and how they expected the relationships they built to extend beyond

Boise. Nearly every student name-dropped while retelling about an inspirational

personal conversation they had with junior and senior level administrators and

coaches from across the conference. “I asked them questions and tried to pick

their brain as much as I could just to be able to gain any knowledge that could

be valuable to me in the sports industry,” SMS-10 reflected. A special panel

discussion organized by the DC specifically for our students on the final day

was mentioned as a highlight for most students. The panel offered advice to our

students on how to break through and succeed in the sports industry. Students

commented on how special it was to hear from the Conference Commissioner,

athletic directors, and other BSC and school administrators. Two students

(SMS-3 and SMS-4) recounted how they sat with one school athletic director

(Montana State University’s) and “engaged in a conversation with him for about

a half hour just picking his brain.” The students both said the athletic

director gave them his personal contact information and encouraged them to stay

in touch. He reportedly also told the students to “give him a call” when they

were ready for a job and if he did not have a place for them at his school, he

would use his connections to help them “land a job” (SMS-3) elsewhere. Students

were thrilled to be able to add their new mentors on their LinkedIn

page, too (students had to set up a LinkedIn page in their Senior

Capstone class). Our students were honored to be invited to a post-event

social hosted by the Conference. “It was really fun to be able to connect with

the Big Sky Conference staff and to be able to let our hair down a little bit

and get to know them on a more personal level after working with them for a

whole week,” SMS-6 wrote.

DISCUSSION

Our current study complements the current body of literature

as it relates to the value of experiential learning. Young, Chung, Hoffman and

Bronkema (2017) found experiences like ours helped students to develop critical

thinking and communication skills, learn problem-solving, and encouraged team

building. Experiences like this have also been shown to help students “maximize

professional development, build professional networks, and gain real-world

experience in the industry” (Brady et al., 2018, p. 36). Like other students in

other studies, our students could actively apply the knowledge they acquired in

the classroom to practical situations (Diacin, 2018). As a result, they are

more likely to retain that knowledge and transfer it to similar situations

(Kolb, 1984). Also, as Pauline (2013) suggested would happen, they gained

self-confidence. Because our students reflected on instances in which they were

expected to apply management theory to address fluid situations appropriately

and independently, we are confident that they actively engaged in all four

stages of the ELT cycle: Experiencing, Reflecting, Conceptualizing and

Experimenting.

Kolb (1984) said that if students are to be effective

learners, they must touch all four bases of the learning cycle. First, students

must be able to involve themselves fully, openly, and without bias in new

experiences. Second, they must be able to reflect on and observe their

experiences from many perspectives. Third, they must be able to create concepts

that integrate their observations into logically sound theories. Fourth, they

must be able to use these theories to make decisions and solve problems.

Through their reflections, we see clear evidence of each of our students

advancing through the ELT cycle. Divergers expressed comfort observing others,

gathering information and then modeling those practices. For example, several

students noted excitement when helping to the transformation of the

championship venue. This included following the DC’s directions on how and

where to lay down court tape and place sponsor logos in preparation for the

tournament. Expressing satisfaction about being part of the successful

completion of the tournament (i.e., being a part of a winning team) was common.

Thus, connecting to the experience on an emotional level was apparent.

Assimilators were more logical. They watched, sought clear explanations,

processed what they learned and designed systematic approaches. Assimilators

have been known to crave the most challenging assignments (Kolb, 1984). SMS-7

gushed about his role in writing game scripts and working in the high stress

environment of the television broadcast team’s. Convergers thrived on the

opportunity to put their own theories into practice, often using a

trial-and-error approach to problem solving. SMS-4, SMS-6 and SMS-9 all wrote

about uncomfortable encounters where coaches and student-athletes were “crying”

or “screaming and punching walls” following team losses. Kolb (1984) warned

that Convergers would find emotional experiences like these as challenging.

Finally, Accommodators took pride in being able to think on their feet and put

their skills into practice. As team hosts, some students recounted instances

they had to react quickly. SMS-9 talked about how he was forced to problem

solve when a team did not vacate their locker room quickly enough and threw

staff and other teams off schedule. Accommodators assumed leadership roles.

They showed initiative and did not need to wait for someone to tell them what

to do. For example, SMS-3 and SMS-6 both volunteered for additional duties

outside their written job description despite their fatigue. Often, this meant

taking risks, but the reward of seeing real time results was more than

satisfying.

Activities like our capstone project are critical to the

learning process. Ours proved to be an impressive outlet for professional

networking, as well. The Association of American Colleges and Universities

(AAC&U) has adopted recommendations made by Kuh (2008) regarding high

impact teaching and learning practices. Such practices are purported to

increase rates of student retention and student engagement amongst college

students (AAC&U, n.d.). Among the recommendations are service learning or

community-based learning activities. AAC&U (n.d.) summarized this

instructional approach:

In these programs,

field-based “experiential learning” with community partners is an instructional

strategy—and often a required part of the course. The idea is to give students

direct experience with issues they are studying in the curriculum and with

ongoing efforts to analyze and solve problems in the community. A key element

in these programs is the opportunity students have to both apply what they are

learning in real-world settings and reflect in a classroom setting on their

service experiences. These programs model the idea that giving something back

to the community is an important college outcome, and that working with

community partners is good preparation for citizenship, work, and life (para.

11).

We feel fortunate to have found such a solid community

partner for our students, ones that truly cared about our student outcomes. We

are also pleased that our students embraced the service-learning component of

this experience.

Throughout the literature we were inundated with examples of

experiential learning as a critical component of sport management education.

This is partly true because the job market is so highly competitive

(Lower-Hoppe et al.,2019; Southall et al., 2003). Already, our capstone experience

has produced measurable results. A current graduate student who took part in

the Boise experience in 2019 and 2020 was chosen for a prestigious internship

at Super Bowl LV. Out of 600 applicants, he was one of 40 chosen to go to

Tampa. He credited his experience working for the Big Sky as an

instrumental factor in his ability to land the highly sought-after job:

What really helped

me land this internship was my willingness to volunteer at the Big Sky

Tournament. It gave me experience working a large-scale championship event. It

also showed the ones overseeing the Super Bowl that I was willing to do what it

takes to achieve my career goals in this industry. (T. Harmon, personal

communication, April 15, 2021)

Evidence from student reflections, survey responses, student

assessments and assures us of the worthiness of this experience. Solicited and

unsolicited feedback from BSC leaders in 2021 was also positive. Our students

were commended for being “hard working” and “personable” (T. Singletary, personal

communication, March 19, 2021). Even the Commissioner of the BSC took note of

the students’ work saying, our students were “a tremendous help” and that his

organization “couldn’t have done it (sic) without them!” (T. Wistrcill,

personal communication, March 19, 2021). The year was particularly challenging

given the uncertainties surrounding COVID-19. That forced our students to be

flexible and adapt to evolving needs. They rose to the occasion. The BSC’s

Senior Associate Commissioner wrote us this:

The crew was amazing

this year. I love this partnership so much. I told them all they were part of

something that the league has never had to do before and hopefully will never

have to do again: We played 20 games in six days in the middle of a global

pandemic. They can be proud of that for the rest of their lives. (J. Kasper,

personal communication, March 19, 2021).

The most rewarding feedback came from the BSC’s administrator

overseeing student-athlete safety:

Let me tell you – I

have worked with so many students over the years and I will say this group was

so refreshing!!!! I have been really down on students and their teachability,

work ethic etc. This group gave me hope for the future. They were the best we

have ever had, and I didn’t hear one complaint. They worked so hard on a couple

of long days – Wednesday started at 6:30am and we didn’t end until midnight –

they got to see the real side of Athletics. They also knew boundaries and

stayed in their lane. They were fantastic. I think this was a great experience

for them as well as us old guys. You are doing so many things right and it is

reflected in your students! (L. Mattice, personal communication, March 19,

2021).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In his book, The Ultimate Guide to Getting Hired in College

Sports, Gauthier (2018) suggested that “breaking into the business

of college sports requires passion for sports, a strong work ethic, sacrifices,

and maybe a little luck” (p. 24). Working with the BSC has undoubtedly exposed

our students to each of these things.

Our evidence here supports the work of Odio, Sagas and Kerwin

(2014), who highlighted the symbiotic value of partnerships like this amongst

all parties involved (e.g., the organization sponsoring the internship, the

student intern, and the academic institution). Following the guidance of

AAC&U, our SMP aims to continue seeking out and partnering with external

groups in an effort to provide our students with additional experiential

learning projects. We are confident in our SMP’s ability to prepare top-notch,

highly qualified professionals in our field.

We encourage other SMP faculty to seek out experiential

opportunities like we had. We realize that many SMPs across the country are

offering similar experiential learning activities utilizing their own

university athletic departments. We have found these activities to be valuable,

too. But for us, those types of on-campus experiences have paled in comparison

to that which our students experienced in Boise. Working for a NCAA, Division I

athletic conference at one of their major championships exposed our students to

a whole-new-level of sport management, one we simply cannot find in or near our

campus town of Pocatello. The pride they felt being part of the BSC team and

the tacit knowledge they acquired about NCAA operations was profound. We found

the leaders of the BSC to be extremely excited about having our students assist

them. BSC staff were not just looking to get volunteers, they truly sought to

mentor our students for the week in Boise and beyond.

The instructional commitment of an experience like this is

time consuming and challenging, as Deluca and Fornatora (2020) warned it would

be. We worked closely with administrators from the BSC for years to fine tune

the student experience. Along the way, the BSC staff explained to us their

needs, and we committed time in the classroom to ensure our students were

prepared. We also spent time searching for and soliciting funding opportunities

to make this experience financially feasible for our students. Being able to

cover the hotel and meal costs associated the travel was a key part in us being

successful in attracting student participants.

We do offer recommendations for those looking to secure

similar opportunities. First, it may be easier for other SMP faculty to choose

learning sites that are more accessible to their students. Our students were

forced to travel a considerable distance and miss other important classes in

the process. Some of our seniors were simply unable to make this commitment.

While choosing a closer site would be an easier approach, we would not change

our approach. We believe traveling to a championship activity away from our

campus and working with industry professionals outside our community presented

benefits we would not have reaped elsewhere. Our students were excited about

being part of a NCAA championship event, and BSC leaders reminded them

frequently just how big of a deal that was. Second, consider how you schedule

your students. Our students’ workdays were long and grueling, but they were

also extremely valuable, and they accurately reflected what sport management

professionals regularly experience. We believe our complete immersion approach

(i.e., work all day for the entire week) was important to our students’ overall

understanding of event management. We also felt exposing them to a myriad of

job tasks throughout the week rather than having them focus on only one area

stimulated their progress through all four phases of Kolb’s experiential

learning cycle. Therefore, we would not recommend simple rotational block

scheduling of students, and we would not recommend having them specialize in

one area (e.g., marketing). Finally, consider the financial implications.

Sending a classroom full of students across the state (region/country) can be

extremely expensive. Because of inflated hotel costs, we incurred about $6,000

worth of expenses in 2021. We were fortunate to find funding, but internal

grants do not offer long-term project sustainability. We are hoping the BSC

will continue to find value and fund the partnership in its entirety in the

future. However, seeking our own external sponsorship might become a necessity

with our hope to continue with this capstone experience.

Acknowledgements

N/A

Funding

N/A

References

Association of American Colleges & Universities (n.d.).

High-impact educational practices: A brief overview.

https://www.aacu.org/node/4084.

Anderson, A. G., Knowles, Z., & Gilbourne, D. (2004).

Reflective practice for sport psychologists: Concepts, models, practical

implications and thoughts on dissemination. The Sport Psychologist, 18(2),

188-203. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.18.2.188

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action:

A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W

H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

Bermingham, A. K., Neville, R. D., & Makopoulou, K.

(2017). Authentic assessment through the sport management practicum:

Participants’ perceptions of the effectiveness of a student-led sports event.

Sport Management Education Journal, 15(1), 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2019-0054

Biddle, S. J., Markland, D., Gilbourne, D., Chatzisarantis, N.

L., & Sparks, A. C. (2001). Research methods in sport and exercise

psychology: Quantitative and qualitative issues. Journal of Sports Sciences,

19(10), 777-809. https://doi.org/10.1080/026404101317015438

Bower, G. G. (2013). Utilizing Kolb’s experiential learning

theory to implement a golf scramble. International Journal of Sport Management

Recreation and Tourism, 12(1), 29-56.

https://doi.org/10.5199/ijsmart-1791-874X-12c

Brady, L., Mahoney, T. Q., Lovice, J. M., and Scialabba, N.

(2018). Practice makes perfect: Practical experiential learning in sport

management. The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation Dance, 89(9), 32-38.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2018.1512911

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. New York:

Vintage Books

Cropley, B., Hanton, S., Miles, A., & Niven, A. (2010).

Exploring the relationship between effective and reflective practice in applied

sport psychology. The Sport Psychologist, 24(4), 521-541.

https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.24.4.521

Deluca, J. R., & Braunstein-Minkove, J. (2016). An

evaluation of sport management student preparedness: Recommendations for

adapting curriculum to meet industry needs. Sport Management Education Journal,

10(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2014-0027.

Deluca, J. R., & Fornatora, E. (2020). Experiential

learning from a classroom desk: Exploring student perceptions of applied

coursework. Sport Management Education Journal, 14, 142-150.

https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2019-0015

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (1998). The

landscape of qualitative research: Theories and issues. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Diacin, M. J. (2018). An experiential learning opportunity for

sport management students: Manager interview and facility inspection. Sport

Management Education journal, 12(1), 114-116.

https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2017-0033

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. D.C. Health & Co.,

Publishers: New York. Retrieved May 18, 2021 from

https://librivox.org/search?title=How+We+Think&author=Dewey&reader=&keywords=&genre_id=0&status=all&project_type=either&recorded_language=&sort_order=catalog_date&search_page=1&search_form=advanced

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation

of reflective thinking to the educative process. Chicago: D. C. Heath.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & Education. New York, NY:

Kappa Delta Pi. ISBN 978-0-684-83828-1.

Gauthier, H. (2018). The ultimate guide to getting hired in

college sports (3rd ed.). Meridian, ID: Sports Leadership Publishing Co.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of

grounded theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Harris, T. H. (2019). Experiential learning – A systematic

review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1570279

Idaho State University Official Student Absence Policy.

(2020). ISUPP 5040. Retrieved from

https://www.isu.edu/media/libraries/isu-policies-and-procedures/student-affairs/Official-Student-Absence-5040.pdf

Knowles, Z., Gilbourne, D., Cropley, B., & Dugdill, L.

(2014). Reflective practice in the sport and exercise science: Contemporary

issues (pp. 4-14). London, UK: Routledge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the

source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the

source of learning and development (2nd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What

they are, who has them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of

American Colleges & Universities. https://www.aacu.org/node/4084

Kurt, S. (2020, December 28). Kolb’s Experiential Learning

Theory & Learning Styles. Educational Technology. https://educationaltechnology.net/kolbs-experiential-learning-theory-learning-styles/

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Legitimate peripheral

participation. In Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, pp.

27-44). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355.003

Lewin, K. (1948) Resolving social conflicts; Selected papers

on group dynamics. Gertrude W. Lewin (ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Lower-Hoppe, L. M., Wanless, L. A., Aldridge, S. M., &

Jones, D. W. (2019). Integrating blended learning with sport event management

curriculum. Sport Management Education Journal, 13, 105-116.

https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2018-0024

Masteralexis, L., Barr, C., & Hums, M. (2011). Principles

and practice of sport management. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

McLeod, S. A. (2017, October 24). Kolb - learning styles and

experiential learning cycle. Simply Psychology.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html

Odio, M., Sagas, M., & Kerwin, S. (2014). The influence of

the internship on students’ career decision making. Sport Management Education

Journal, 8(1), 46-57. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2013-0011.

Pauline, G. (2013). Engaging students beyond just the

experience: Integrating reflection learning into sport management. Sport

Management Education Journal, 7(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.7.1.1

Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child.

London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Piaget, J. (1945). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood.

London: Heinemann.

Sang, K. J. C., & Sitko, R. (2015) Analysing qualitative

data. In Research Methods for Business and Management. (2nd ed., pp. 137-152).

Oxford: Good Fellow Publishers. https://doi.org/10.23912/978-1-910158-51-7-2775

Sattler, L., & Aichen, R. (2021). A foot in the door: An

examination of professional sport internship job announcements. Sport

Management Education Journal, 15(1), 11-19.

https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2019-0059

Sato, T. & Laughlin, D. D. (2018). Integrating Kolb’s

Experiential Learning Theory into a sport psychology classroom using a

golf=putting activity. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 9(1), 51-62.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1325807

Selingo, J. J. (2016). There is life after college: What

parents and students should know about navigating school to prepare for the

jobs of tomorrow. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Southall, R. M., Nagel, M. S., LeGrande, D., & Han, P.

(2003). Sport management practica: A metadiscrete experiential learning model.

Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(1), 27-36.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative

research: Grounded theory, procedures, and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Strong, R. (2013, October 15). ‘Education is not the filling

of a pail, but the lighting of a fire’: It’s an inspiring quote, but did WB

Yeats say it? The Irish Times.

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/education-is-not-the-filling-of-a-pail-but-the-lighting-of-a-fire-it-s-an-inspiring-quote-but-did-wb-yeats-say-it-1.1560192

Wolpert-Gowron, H. (2016, November 7). What the heck is

service learning? Edutopia.

https://www.edutopia.org/blog/what-heck-service-learning-heather-wolpert-gawron

Young, D. G., Chung, J. K., Hoffman, D. E., & Bronkema, R.

(2017). 2016 national survey of senior capstone experiences: Expanding our understanding

of culminating experiences (Research Report No. 8). National Resource Center

for the First-Year Experience and Students in Transition, University of South

Carolina.

*Address correspondence to:

Caroline E. Faure, EdD, ATC-L

Department of Human Performance

and Sport Studies

Idaho State University

Pocatello, ID 83209

Email: smittyfaure@isu.edu

Journal of Kinesiology and Wellness ©

2021 by Western Society for Kinesiology and Wellness is licensed

under CC

BY-NC-ND 4.0.c