Recent studies have been conducted on the

status of physical education service programs (also called basic instruction

programs, activity programs, or physical education requirements) in colleges

and universities within the states of Colorado (Heumann & Murray, 2019) and

Oregon (Szarabajko et al., 2021). Both of these states encompass part of the

representative area of the Western Society for Kinesiology and Wellness (WSKW).

This study is a continuation of research on the topic, but is focused on the

state of Utah, where the first meeting of the WSKW was held in 1956 on the

campus of the University of Utah (WSKW, n.d.).

Physical education has over a 150-year-old

history in American academe, dating to the mid-1800s when Amherst College began

the first physical education program in American higher education (Allen,

1869). Physical education’s original purpose – and one could argue its primary

purpose still – is to “help students develop personal awareness and

responsibility regarding healthy lifestyle choices,” especially related to

physical activity (Szarabajko et al., 2021, p. 56). However, physical

education, particularly as a graduation requirement, has been eroding

throughout American academe over the last few decades (Cardinal, 2020).

While once plentiful in American higher

education, physical education service programs often are voluntary instead of

required. Even more troubling is that they frequently are being substituted for

elective recreational programming (Kim & Cardinal, 2019a; Kim & Cardinal,

2019b), which often caters to those already active and does not reach the

entire student population the way required physical education would.

Essentially, most students in the US today are not required to learn health and

fitness skills during their collegiate experience, and without required

physical education, “a large number of inactive and unmotivated students

continue to be neglected… [and they] are the students who may benefit the most

from [physical education requirements]” (Szarabajko et al., 2021, p. 57).

Further, historical data indicate very few collegiate students (i.e., 3.43%)

use campus recreational facilities regularly (Zakrajsek, 1994), and often the

population not participating is made up of those most “historically

disenfranchised in society” (Cardinal, 2020, p. 288; Hoang et al., 2016). If

these data are accurate, American academe is failing an estimated 96.57% of the

student population, or some 20 million students each year, with respect to

proper physical education (Cardinal, 2017). More recent survey data suggest

only 39 percent of students report they participated in campus recreational

activities a minimum of three times per week (Forrester, 2014). The most recent

national data show 42 percent of college students meet the recommended level of

physical activity, i.e., 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity

(American College Health Association [ACHA], 2021), corroborating the 2014

data. As with all research, limitations exist, especially with self-reported

data, but the low to modest percentage of college students being active in

voluntary recreational programming is worrisome. These facts become even more

disconcerting as research indicates that during the collegiate years, students

tend to become less active (Nelson et al., 2007; Small et al., 2013), gain

unhealthy weight (Pope et al., 2017; Yan & Harrington, 2020), and undergo

more negative stress (Petruzzello & Box, 2020), which results in the

adoption of lifelong detrimental health behaviors (Sparling, 2003). It is

precisely the opposite of what the results should be for a well-rounded

undergraduate education.

The importance of physical education is

undeniable, as considerable research indicates that physical activity is

essential for sound health (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC],

n.d.). In addition to building robust health in the form of such things as

cardiovascular fitness (Warburton & Bredin, 2017) and combating obesity

(World Health Organization [WHO], 2010), physical activity, especially on the collegiate

level, has been shown to positively affect the knowledge and attitudes as well

as the lifelong behaviors of alumni (Pearman III et al., 1997), build social

connections (VanKim & Nelson, 2013), develop positive health behaviors

(Quartiroli & Maeda, 2016), increase academic performance and retention

rates (Chang et al., 2014; Sanderson et al. 2018), enhance mental health

(Currier et al., 2020; Petruzzello & Box, 2020), and promote public health

(Cardinal, 2016). Further, undergraduate students are desiring that

institutions of higher education offer physical activity courses for physical,

mental, social, and academic needs (Lackman et al., 2015), and a positive

relationship exists between physical fitness and academic achievement (Donnelly

et al., 2016).

These facts, unfortunately, often are

ignored by administrators and faculty on college and university campuses, and

those overseeing physical education programming frequently must justify their

existence regularly despite the existing and growing evidence that required

physical education is effective (Cardinal, 2017, 2020). Regrettably, many in

physical education are losing the battle, as required physical education has

been decreasing on American college and university campuses in favor of

voluntary physical education activity programs (including dance programs) or

campus recreational programming or some combination of these programs.

The national trend is that fewer

institutions of higher education are requiring physical education as a

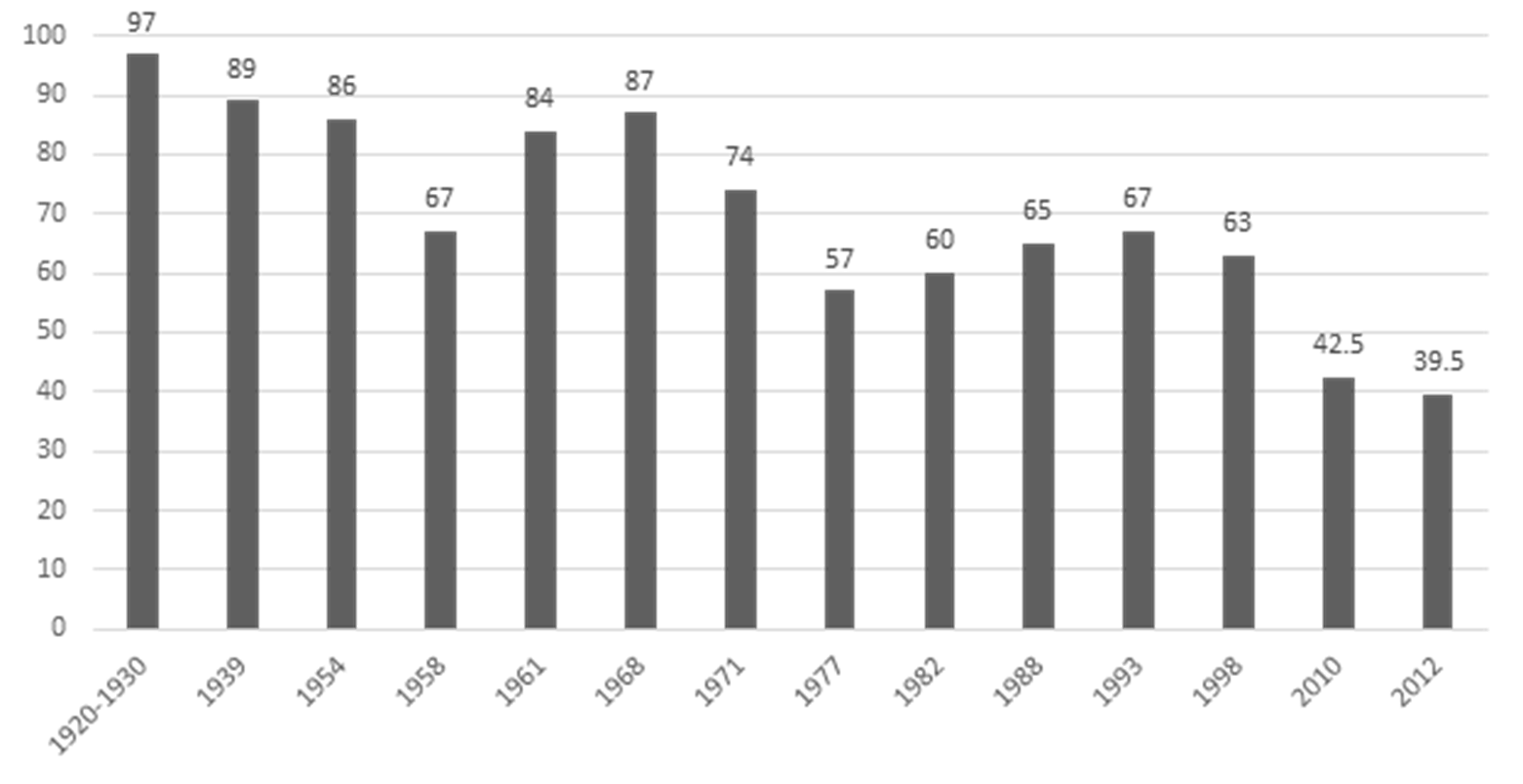

graduation requirement (Cardinal, 2020). Over the last century, previous

researchers (See Figure 1) have investigated the national status of physical

education service programs (Boroviak, 1989; Cardinal et al., 2012; Cordts &

Shaw, 1960; Hensley, 2000; Hunsiker, 1954; McCristal & Miller, 1939; Miller

et al., 1989; Oxendine, 1961, 1969, 1972; Oxendine & Roberts, 1978; Strand

et al., 2010; Trimble & Hensley, 1984, 1990). The findings from these

studies show that during the 1920s and 1930s, nearly all institutions (97%)

required physical education, and that percentage generally held steady –

between 84 to 87 percent – through the 1960s (Heumann & Murray, 2019). By

the 1990s, the percentage averaged in the mid-60s, in 2010, the number had

dropped to 42.5 percent, and by 2012, an all-time low of 39.5 percent occurred

(Cardinal et al., 2012). Although these studies had limitations, and current

data are needed, the trend is alarming.

Eliminating required physical education and

wellness programming on the collegiate level has been shown to negatively

affect students’ health-related behaviors. Ansuini (2001) found that within 3

years of terminating the wellness/physical activity requirement, one

institution incurred a “marked decrease in campus well-being” related to diet,

exercise, and other habits and concluded, “[t]he magnitude of these results

should reaffirm the need for mandatory wellness/activity programming” (p. 455).

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in March 2020, altered the

general behaviors of most college students, influencing their overall health

and wellness. Studies have shown that the pandemic triggered a decrease in

physical activity levels and an increase in mental health concerns among

college students (Dziewoir et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 2021). Given the

ongoing effects of the pandemic, research investigating physical education

course offerings is increasingly relevant.

The value of physical education service

programming is incontrovertible, and required programs seem to be more

effective than voluntary ones. Nonetheless, the data on the status of physical

education programming are not up to date, and a state-by-state analysis is

needed, as recommended by Heumann and Murray (2019). Using the two previous

studies conducted on the state level for Colorado and Oregon, respectively, as

models, this study was undertaken to examine the status of physical education

service programs in the colleges and universities of the state of Utah.

METHODS

Participants

A list of all institutions (n = 23) of

higher education in the state of Utah was obtained from the website of the

National Center for Education Statistics (2021). For-profit and specialized

schools (e.g., midwifery, computer science, online, post-graduate; n = 13) were

removed from the list, as they normally do not offer physical education service

programming nor general education courses, and that left 10 (2 private; 8

public), traditional, not-for-profit institutions of higher education on the

list. Of those, 9 were 4-year institutions, and 1 was a 2-year institution. A

traditional institution was defined as a brick-and-mortar school, offering a

comprehensive curriculum, with a general education component, often based in

the liberal arts.

Procedure

Using the methodological examples of the

previous studies (Heumann & Murray, 2019; Szarabajko et al., 2021),

publicly available information was obtained via each institution’s website. The

methods included searching the internet sites of each institution to examine

the official catalogs (2020-2021) and the listed graduation requirements for

students to earn an associates or baccalaureate degree. The course listings

were examined as well to search for elective courses. We used the same

operational definition as Tomaino et al. (2001) for physical education: “Physical education was considered any activity or academic

course pertaining to health, wellness, sports, or physical activity. For the

course to be considered ‘required,’ it had to be listed by the institution as a

requirement for graduation. If not, it was considered an elective” (Tomaino et

al., 2001, p. 10). Additional information such as the types of courses offered

was collected, and this differed from the two previous studies on Colorado and

Oregon that were used as models. To be able to compare better to the Oregon

study’s results, the

availability of a campus recreation center and accompanying programming was

searched for as well.

Analysis

Data analysis was conducted by determining

the current number of 4-year and 2-year colleges and universities. After

reviewing the catalogs, the total number of programs that required these

courses also was calculated. The percentage was then calculated by reporting

the total number required out of the total number of institutions at that

level.

RESULTS

The requirements of the physical education

service programming in Utah’s colleges and universities are presented in Table

1. All institutions (100%; 10 of 10) had physical education service programs

offering a wide array of courses to their students (see Table 2). One-half of

the institutions (50%; i.e., 5 of 10) either required (10%; i.e., 1 of 10) or

partially required (40%; i.e., 4 of 10) physical education as a graduation

requirement; partially requiring physical education meant that some degrees

required some sort of physical education course, or physical education courses

were listed as an option to fulfill a specific requirement. The only

institution that required physical education for every student was the lone

2-year institution in the state. Each institution (100%, i.e., 10 of 10) had a

campus recreation center with associated programming.

DISCUSSION

The status of required physical education in

Utah’s colleges and universities is low, at 10 percent (1 out of 10), and

compares similarly to Colorado, at 15.6 percent (5 of 32) and Oregon, at 14.29

percent (5 of 35). Heumann and Murray (2019) noted Colorado’s rate has dropped

from 41 percent in 2001 and is well below the latest-available national rate of

39.5 percent (Cardinal et al., 2012). The current national rate is unknown, as

the last national study was published nearly 10 years ago, but the trend, especially

from these studies on Colorado, Oregon, and Utah, indicates that it may be

dropping well below 39.5 percent. Additional states need to be studied for

required physical education at the higher-education level to get a clearer

position of the trend to see if these states are outliers or predictors.

On a more positive note, physical education

service programs in Utah’s colleges and universities are universal and robust,

with every institution (10 of 10, or 100%) providing a wide range of physical

education courses. That is a promising statistic, and it is a greater

percentage than what was found for both Colorado (27 of 32, or 84.4%; Heumann

& Murray, 2019) and Oregon (30 of 35, or 85.7%; Szarabajko et al., 2021).

Moreover, each institution (10 of 10, or 100%) also had a campus recreation

center, with accompanying programming. Data are not readily available for

campus recreation centers in Colorado, but Utah’s 100-percent rate for both

4-year (i.e., 9 of 9) and 2-year (i.e., 1 of 1) institutions far exceeds the

values found for Oregon’s higher-education institutions. Szarabajko et al.

(2021) reported that of the Oregonian 4-year and 2-year institutions of higher

education, 83.33 percent (i.e., 15 of 18) and 47.06 percent (i.e., 8 of 17),

respectively, had campus recreation centers.

The reason for Utah’s institutions of higher

education having such plentiful programs in physical education and recreation

is unknown. One possible explanation could be related to the philosophical

founding of the state and its citizenry. Utah was founded by pioneers of the

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). Approximately 61

percent of the state’s population are members of the LDS Church (Canham, 2018),

and maintaining physical fitness has long been stressed by the LDS Church’s

teachings (Kimball, 2003; Robinson, 1972; Thorstenson, 1984). Further, Utah is

well known for its outdoor recreational pursuits (e.g., hiking, skiing), and it

has well-developed physical education programming in its primary and secondary

schools (Utah State Office of Education, 2016). While both Colorado and Oregon

are known for their outdoor activities, their citizens do not share a similar

background philosophically like the majority of Utahans do. Perhaps this could

be a contributing factor, but specific research on this possibility is needed.

Colorado, Oregon, and Utah are states that

rank as some of the most physically active in the country (CDC, 2021), which

may explain why physical education service programs are plentiful, but not

required, in their colleges and universities. As more research is gathered on a

state-by-state level with respect to physical education programming in tertiary

education, regional and national trends should become apparent. The

relationship between each state’s physical activity ratings and its collegiate

physical education programming is an unknown yet interesting area of research

and one worthy of exploration.

A major incentive for supporting required

physical education in the curricula of colleges and universities is the

promotion of individual wellness, and therefore by extension, public health

(Cardinal, 2020). Many collegiate administrators today openly support the

education of the whole student through a mind-body-spirit approach (National Association

of Student Personnel Administrators [NASPA], (2017),

or what essentially is the original model of wellness that Dunn (1959) defined.

As with all studies, limitations exist. In

this study, all data were taken from the most up-to-date information available

from each institution’s website, but the precise offerings for each institution

are unknown. Further, the filtering of the institutions based on the

traditional brick-and-mortar criterion was a limitation and affected the sample

size.

CONCLUSION

Physical education service programs have

been involved in American higher education since the mid 1800s. The first

programs centered on the prevention of illness through physical activity.

Cardinal et al. (2021, p. 509) indicated that just as the founders of

collegiate physical education knew and implemented, “prevention comes before

cure,” and that approach is necessary today with required physical education.

Heumann and Murray (2019) made a call for more state-level research on the

status of physical education in colleges and universities. Szarabajko et al.

(2021) answered that call with data from Oregonian institutions. This study has

provided data on Utah’s institutions of higher education and serves as another

step in gaining accurate and up-to-date data on the status of physical

education within the institutions of the areas that constitute the scholars of

the Western Society for Kinesiology and Wellness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the

assistance of Christine Murgida for data collection.

FUNDING

N/A

REFERENCES

Allen, N. (1869). Physical culture in Amherst

College. Stone & Huse.

American College Health Association. (2021).

National college health assessment: Undergraduate student reference group. https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-III_SPRING-2021_UNDERGRADUATE_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY_updated.pdf.

Ansuini, C. G. (2001). The impact of

terminating a wellness/activity requirement on campus trends in health and

wellness [Abstract]. American Journal of Health Promotion, 15(6), 455. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-15.6.453.

Boroviak, P. C. (1989). The status of

physical education basic instruction programs in selected large universities in

the United States. The Physical Educator, 46, 209–212. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/status-physical-education-basic-instruction/docview/1437929545/se-2?accountid=14496.

Canham, M. (2018, December 9). Salt Lake

County is now minority Mormon, and the impacts are far reaching. Salt Lake

Tribune. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2018/12/09/salt-lake-county-is-now/.

Cardinal, B. J., Sorensen, S.D., &

Cardinal, M.K. (2012). Historical perspective and current status of the physical

education graduation requirement at American 4-year and colleges and

universities. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 83(4), 503-512. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2012.10599139.

Cardinal, B. J. (2020). Promoting physical

activity education through general education: Looking back and moving forward.

Kinesiology Review, 9(4), 287-292. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2020-0031.

Cardinal, B. J. (2017). Quality college and

university instructional physical activity programs contribute to mens sana in

corpore sano, “the good life,” and healthy societies. Quest, 69(4), 531–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2017.1320295.

Cardinal, B. J. (2016). Physical activity

education’s contributions to public health and interdisciplinary studies:

Documenting more than individual health benefits. Journal of Physical

Education, Recreation, and Dance, 87(4), 3-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2016.1142182.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Physical activity: Why it matters. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/about-physical-activity/why-it-matters.html.

Chang, Y. K., Chi, L., Etnier, J. L., Wang,

C. C., Chu, C. H., & Zhou, C. (2014). Effect of acute aerobic exercise on

cognitive performance: Role of cardiovascular fitness. Psychology of Sport and

Exercise, 15(5), 464–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.04.007.

Cordts, H. J., & Shaw, J. H. (1960).

Status of the physical education required or instructional programs in

four-year colleges and universities. The Research Quarterly, 31, 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10671188.1960.10762047.

Currier, D., Lindner, R., Spittal, M. J.,

Cvetkovski, S., Pirkis, J., & English, D. R. (2020). Physical activity and

depression in men: Increased activity duration and intensity associated with

lower likelihood of current depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260,

426–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.061.

Donnelly, J. E., Hillman, C. H., Castelli,

D., Etnier, J.L., Lee, S., Tomporowski, P., et al. (2016). Physical activity,

fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: a systematic

review. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 48(6), 1197-1222. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000901/.

Dunn, H. L. (1959). What high-level wellness

means. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 50(11), 447-457. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41981469.

Dziewior, J, Carr, L., Pierce, G., &

Whitaker, K. (2021). Physical activity and sedentary behavior in college

students during the Covid-19 pandemic. Medicine and Science in Sports and

Exercise, 53(85), 184-185. https://doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000761204.78353.d8.

Forrester, S. (2014). The Benefits of Campus

Recreation. NIRSA. https://nirsa.net/nirsa/wp-content/uploads/Benefits_Of_Campus_Recreation-Forrester_2014-Report.pdf

Hensley, L. D. (2000). Current status of basic

instruction program in physical education at American colleges and

universities. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 71(9),

30–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2000.10605719.

Heumann, K. J., & Murray, S. R. (2019).

The status of physical education in Colorado’s colleges and universities.

Journal of Kinesiology and Wellness, 8(1), 29–35. https://jkw.wskw.org/index.php/jkw/article/view/55/101.

Hoang, T. V., Cardinal, B. J., & Newhart,

D. W. (2016). An exploratory study of ethnic minority students’ constraints to

and facilitators of engaging in campus recreation. Recreational Sports Journal,

40(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1123/rsj.2014-0051.

Hunsiker, P. A. (1954). A survey of service

physical education programs in American colleges and universities. Annual

Proceedings of the College Physical Education Association, 64(6), 29–30.

Kim, M. S., &

Cardinal, B. J. (2019a). Differences in university students’ motivation between

and an elective physical activity education policy. Journal of American College

Health, 67(3), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1469501.

Kim, M. S., &

Cardinal, B. J. (2019b). Psychological state and behavioural profiles of

freshman enrolled in college and university instructional physical activity

programmes under different policy conditions. Montenegrin Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 8(2), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.26773/mjssm.190902.

Kimball, R. I. (2003). Sports in Zion: Mormon

recreation, 1890-1940. University of Illinois Press.

Lackman, J., Smith, M. L., & McNeill, E.

B. (2015). Freshman college students’ reasons for enrolling in and anticipated

benefits from a basic college physical education activity course. Frontiers in

Public Health, 3, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00162.

McCristal, K. J., & Miller, E. A. (1939).

A brief survey of the present status of the health and physical education

requirement for men students in colleges and universities. Research Quarterly,

10(4), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10671188.1939.10622514.

Miller, G. A., Dowell, L. J., & Pender,

R. H. (1989). Physical activity programs in colleges and universities. Journal

of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 60(6), 20–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1989.10604474.

National Association of Student Personnel

Administrators (NASPA) Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education. (2017,

October 17). A new model for campus health: Integrating well-being into campus

life. https://www.naspa.org/about/blog/a-new-model-for-campus-health-integrating-well-being-into-campus-life.

National Center for Education Statistics.

College Navigator. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/.

Nelson, T. F., Gortmaker, S. L., Subramanian,

S. V., & Wechsler, H. (2007). Vigorous physical activity among college

students in the United States. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 4(4),

496–509. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.4.4.496.

Oxendine, J. B. (1961). The service program

in 1960–61. Journal of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, 32(6),

37–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221473.1961.10621388.

Oxendine, J. B. (1969). Status of required

physical education programs in colleges and universities. Journal of Health,

Physical Education, and Recreation, 40(1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221473.1969.10613887.

Oxendine, J. B. (1972). Status of general

instruction programs of physical education in four-year colleges and

universities: 1971–72. Journal of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation,

43(3), 26–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221473.1972.10617245.

Oxendine, J. B., & Roberts, J. E. (1978).

The general instruction program in physical education at four-year colleges and

universities: 1977. Journal of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, 49(1),

21–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00971170.1978.10617651.

Pearman III, S. N., Valois, R. F., Sargent,

R. P., Drane, J. W., & Marcera, C. A. (1997). The impact of a required

college health and physical education course on the health status of alumni.

Journal of American College Health, 46(2), 77-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448489709595591.

Petruzzello, S. J., & Box, A. G. (2020).

The kids are alright—Right? Physical activity and mental health in college

students. Kinesiology Review, 9(4), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2020-0039.

Pope, L., Hansen,

D., & Harvey,

J. (2017). Examining

the weight trajectory of college students. Journal of Nutrition

Education and Behavior,

49(2), 137–141.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2016.10.014.

Quartiroli, A. & Maeda, H. (2016). The

effect of a lifetime physical fitness (LPF) course on college students’ health

behaviors. International Journal of Exercise Science, 9(2), 136-148. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4882468/.

Robinson, C. F. (1972). Keeping physically

fit. Ensign, 2(9). https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/1972/09/keeping-physically-fit?lang=eng.

Sanderson, H., DeRousie, J., & Guistwite,

N. (2018). Impact of collegiate recreation on academic success. Journal of

Student Affairs Research and Practice, 55(1), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2017.1357566.

Small, M., Bailey-Davis, L., Morgan, N.,

& Maggs, J. (2013). Changes in eating and physical activity behaviors

across seven semesters of college: Living on or off campus matters. Health

Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public

Health Education, 40(4), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198112467801.

Sparling, P. B. (2003). College physical

education: an unrecognized agent of change in combating inactivity-related

diseases. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(4), 579-87. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2003.0091.

Strand, B., Egeberg, J., & Mozumdar, A.

(2010). Health-related fitness and physical activity courses in U.S. colleges

and universities. The International Council for Health, Physical Education,

Recreation, Sport, and Dance Journal of Research, 5(2), 17–20. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ913327.

Szarabajko, A., Campos-Hernandez, V. J., & Cardinal, B. J.

(2021). Physical education graduation requirements in Oregon’s

tertiary institutions. Journal of Kinesiology and Wellness, 10(1), 56-64. https://jkw.wskw.org/index.php/jkw/article/view/91/163.

Thorstenson, C. T., (1984). The Mormon

commitment to family recreation, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and

Dance, 55(8), 50-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1984.10630628.

Tomaino, L. Murray, S.R, & Yeager, S.A.

(2001). The status of required physical education in the curriculum of Colorado

colleges and universities. CAHPERD Journal, 26(1), 10-12.

Trimble, R. T., & Hensley, L. D. (1984).

The general instruction program in physical education at four-year colleges and

universities: 1982. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 55(5),

82–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1984.10629778.

Trimble, R. T., & Hensley, L. D. (1990).

Basic instruction programs at four-year colleges and universities. Journal of

Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 61(6), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1990.10604555.

Utah State Office of Education. (2016). Utah

core state standards for physical education. https://www.schools.utah.gov/file/6192280d-2ab2-4ff1-b5dd-a9c2f95c1b11.

VanKim, N. A., & Nelson, T. F. (2013). Vigorous physical activity, mental health, perceived stress, and

socializing among college students. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 28(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.111101-QUAN-395.

Warburton, D. E. R., & Bredin, S. S. D.

(2017). Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current

systematic reviews. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 32(5), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437.

Western Society for Kinesiology and Wellness.

Our history: A brief history of the Western Society for Kinesiology &

Wellness. Retrieved November 22, 2021 from https://www.wskw.org/our-history/.

Wilson,

O. W., Holland, K. E., Elliott, L. D., Duffey, M., & Bopp, M. (2021). The

impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on US college students’ physical activity and

mental health. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 18(3), 272-278. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2020-0325.

World Health Organization. (2010). Global

recommendations on physical activity for health. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44399/9789241599979_eng.pdf;jsessionid=23C853E45F6225D2E32F614727F364BA?sequence=1.

Yan, Z., & Harrington, A. (2020). Factors

that predict weight gain among first-year college students. Health Education

Journal, 79(1), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896919865758.

Zakrajsek, D. M. (1994).

Basic instruction: Utility or futility? Journal of Physical Education,

Recreation& Dance, 65(9), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1994.10606997.